I Was Diagnosed with Incurable Cancer. This Futuristic Treatment Could Save Me.

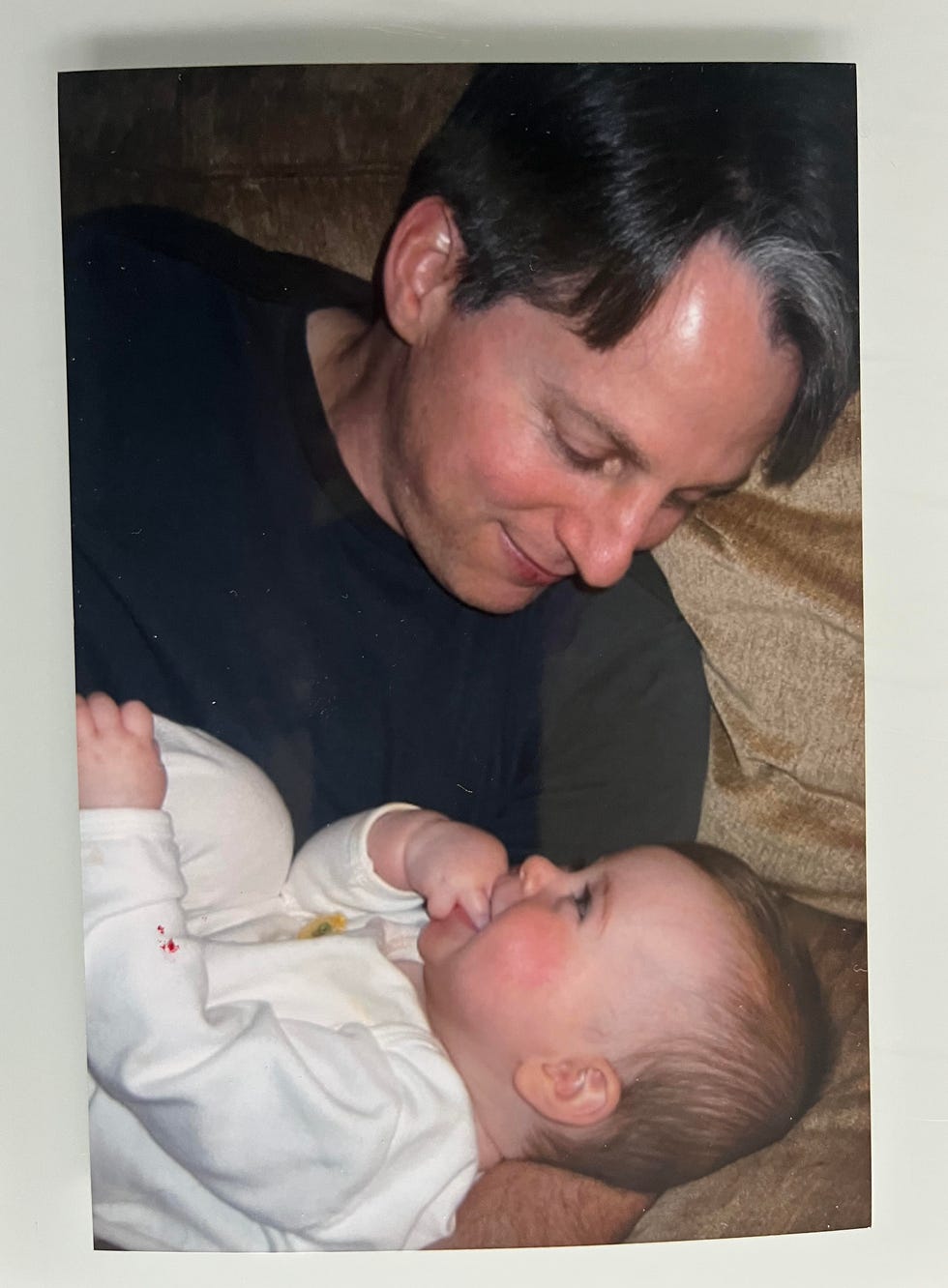

In the fall of 2003, I slipped on the ice leaving my office one night. My hip hurt for a year afterward, but mostly I ignored it. When the pain didn’t go away, I saw my doctor, who ordered an MRI. I went to his office, and he told me there was a tumor on my hip. I was 38 years old, pursuing a promising career in journalism, married to a woman I loved, and the first-time father of a seven-month old daughter.

At the time I was diagnosed with the type of cancer it turned out I have, a rare and incurable form of blood cancer called multiple myeloma, I was told I had eighteen months to live. That was more than twenty one years ago.

In those twenty one years, I have undergone a barrage of treatments to combat my disease. They include four rounds of radiation therapy (to my hip, neck, ribs, and nose); a six-month course of weekly intravenous immunotherapy (followed by seven years of a maintenance level of that therapy taken in pill form); another two-year round of immunotherapy involving the next-generation versions of the previous drugs I was on, in pill form; a third-round of immunotherapy involving two new immunotherapy drugs administered weekly by IV for two more years; and six years (and counting) of monthly IV infusions of an agent used to boost my immune system, which has been compromised both by my disease and the treatments used to fight it. But the most remarkable treatment I’ve had so far is a cutting-edge procedure, approved by the FDA for use in cases like mine only in 2022, called CAR-T therapy. This is the story of that treatment.

This time, I didn’t slip on the ice. I bent over to load the dishwasher and felt a stab of pain in my back. It was February of 2023. My oncologist, Dr. Sundar Jagannath at Mount Sinai hospital in New York City, ordered a series of blood tests and scans. They showed I had come out of remission again, for the seventh time. I had tumors on my hip, in my ribs, and in my thoracic and lumbar spine.

On an incongruously lovely day in March, my wife, Didi, and I met with Dr. Jagannath. My best treatment option, he explained, was a virtually brand-new, cutting-edge, almost mind-blowingly futuristic type of immunotherapy called CAR-T therapy. It would be the most powerful, and dangerous, treatment I had had to date.

CAR-T therapy involves harvesting T-cells from your bloodstream, then sending them to a lab where a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, is added to the surface of the T-cells (hence the acronym “CAR-T”). The CAR protein helps the T-cells recognize antigens found on the surface of specific cancer cells, in my case myeloma cells, so the T-cells can target and kill the malignant cells. The CAR-charged T-cells are then infused back into your body intravenously to do their work.

When I started CAR-T, my wife, Didi, and I had dozens of questions.

CAR-T is a so-called one-and-done therapy; it requires little ongoing maintenance care, he explained. If it worked, I could go back to living a relatively normal life, at least for a time, with little or no maintenance therapy required.

Naturally, there were caveats. CAR-T is by no means 100-percent effective, it requires months of preparation, some of it complex and unpleasant, and it has a number of potentially debilitating, and sometimes fatal, side effects.

The scientific definition of “chimera”—the key word in chimeric antigen receptor—is a part of the body made up of tissues of diverse genetic material, but the term has two other meanings. One is an imaginary monster made up of incongruous parts. The other is an illusion, more specifically an unrealizable dream. Both seemed apt.

Because CAR-T is a complex and highly specialized therapy, Dr. Jagannath referred me to a CAR-T specialist to manage my treatment. Didi and I had our first appointment with Dr. Shambavi Richard several weeks later.

An Indian-American woman with long black hair who favors stylish eyeglasses, Dr. Richard balances a friendly, easygoing manner with deep professional expertise.

The CAR-T preparation, she explained, was indeed complex. In my case, it would include dozens of blood tests; both a bone biopsy and a bone marrow biopsy; a procedure to harvest my T-cells; possibly more radiation if the tumors in my bones became problematic before I received my CAR-T (it takes roughly a month after the T-cell harvest for the turbocharged cells to be manufactured); a four-day hospital stay to administer a chemotherapy regimen known as DCEP meant to reduce the number of myeloma cells in your body to make the CAR-T treatment more effective; three days of an outpatient treatment called lymphodepletion, another form of chemotherapy, that kills off your existing T-cells to help the bioengineered T-cells attack the myeloma cells more effectively; and the placement of a catheter in my chest that would be used to infuse the CAR-T cells, administer related medicines, and draw blood to monitor my blood counts during the two-week hospital stay the CAR-T infusion requires.

The two most serious side effects of CAR-T therapy, she told us, are Cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity. Cytokine release syndrome, or CRS, occurs when the body’s immune system responds too aggressively to an infection. In the case of CAR-T therapy, the body seems to mistake the bioengineered cells for an infection, triggering the unwelcome response. The symptoms of CRS include fever and chills (“shake and bake” as some doctors call it), fatigue, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, headaches, cough, and low blood pressure. If not treated quickly, the condition can be fatal.

Neurotoxicity is a broad term for a set of neurological symptoms that can include headaches, confusion, delirium, slurred or incoherent speech, seizures, and cerebral edema, or swelling of the brain. It, too, can be deadly if it isn’t treated immediately.

CAR-T therapy also leaves patients seriously immunocompromised and open to infections for months and sometimes years afterward. It wipes out their immune systems so thoroughly, they eventually need to get all their childhood immunizations (mumps, measles, rubella, etc.), not to mention COVID and flu shots, again. Until they get those shots, which can’t be done until at least six months after CAR-T, they are susceptible to all those illnesses and more. During my hospital stays, I would be allowed only a limited number of visitors, and they would all have to be masked. After I went home, I would have to live more cautiously than I had been, the way we all did in the early days of COVID.

I was diagnosed with myeloma at 38 years old, when I was a new father.

Didi and I had dozens of questions. Wait, how does CAR-T work again? Would the T-cell harvest cause the same fire-ant tingling my stem-cell harvest had caused? Would I be able to attend my niece’s wedding on Cape Cod in August?

In addition to being a world-class physician, Dr. Richard is a first-rate listener. She patiently answered all our questions, told us her office would arrange the necessary appointments for us, and sent us on our way.

Didi and I took a cab home. As we made our way down Fifth Avenue, we felt strangely optimistic. Action is better than inaction. And I was going to be bionic.

I did the blood tests. I did the biopsies. I did the T-cell harvest. I didn’t wind up needing radiation.

In preparation for losing my hair during the two rounds of chemotherapy, I got a buzz cut. It seemed to me that losing short pieces of hair would be less traumatic than losing long strands of it. When my barber remarked it was a dramatic choice for me, I lied and said I wanted to keep cool for the summer. Then, on Thursday, May 11, I checked into Mount Sinai to start my four-day DCEP treatment.

“DCEP” is a loose acronym for “Dexamethasone, Cyclophosphamide, Etoposide, and Cisplatin,” the four drugs that make up the regimen. They are administered intravenously. By four o’clock that afternoon, I was ensconced in my room on the eleventh floor of the hospital and hooked up to an IV pole.

Because DCEP must be given continuously, I was attached to my IV around the clock. I have been hooked up to many IVs, and I am here to tell you that the electronic pumps used to deliver them are glitchy. The most annoying part is that the alarms the devices are equipped with, which are supposed to go off only when there is a problem with the flow of the medication, frequently go off for no reason. Every time that happens a nurse has to come, check to be sure everything is okay, and reset the pump. When you are on a pump twenty-four hours a day, this can be maddening. It is certainly not conducive to sleeping.

After four days in the hospital, I was more than eager to go home. Physically, I felt fine. Luckily, I had tolerated the DCEP with almost no side effects. But I felt exhausted from not sleeping much and emotionally wrung out.

Just after dinner on my fourth day, I was discharged.

The next morning, after my son, Oscar, had gone to school, I sat down on the couch in our living room. Didi was at the dining room table, working on her laptop.

“You know what’s nice?” I said.

From the time I had left for the hospital until that moment, I hadn’t felt especially scared or upset. Mostly, for the ninety-six hours I was at Mount Sinai, I had just put my head down and did what I needed to do.

I started to answer my own question. What I had intended to say was, “Sleeping in your own bed.” But before I could finish the sentence, all the emotions I had apparently repressed over the previous four days in the hospital, or maybe the previous nineteen years, came rushing to the surface.

Despite successful treatment, I remain afraid of leaving my son, Oscar, and my daughter, A.J., without a father.

I’m a relatively stoic person. I’m not easily overwhelmed by my problems. I’m not even particularly inclined to talk about them.

Well, cancer makes liars of stoics. Just as it attacks your body, it attacks your emotional defenses, and doesn’t stop until it strips you of them. You want to put up a fight for nineteen years? That’s okay. Cancer is patient. Cancer will wait. It laughs at your perseverance. It mocks your stiff upper lip. It is amused by your courage. Eventually, it will break you. You may enter cancer as a stoic, but you will not leave as one.

I started crying. Bawling, really. A deep, primal, ugly wail. It was the first time I had cried that hard since I was first diagnosed. Contrary to my stoic instincts, crying didn’t make me feel weak or ashamed. It made me feel relieved. It felt like nineteen years of weight had been lifted off my shoulders.

“I missed you guys so much,” I managed to say to Didi between gasps for breath. “I am so glad to be home.”

I’ve been asked if I’m afraid of dying. The answer is no, not really. Having been forced to think long and hard about the subject, I’ve come to terms with it. In my view, death is death. No heaven or hell. Just worm food. Nothingness. Why should I be afraid of nothing?

What I am afraid of is suffering. I have seen suffering up close, in oncologists’ offices, in treatment facilities, and on cancer wards. It is decidedly scary.

During my radiation treatments, I have seen patients with skin burns so severe they look like arson victims. During my treatment sessions, I have seen a gentleman wet his pants in his chair while he was sleeping; a woman collapse on her way to the bathroom, split her head open, and bleed all over the floor; and toilets covered in splatter from diarrhea. During my hospital stays, I have seen patients who were bald, emaciated, and as pale as the hospital-white blankets they were wrapped in to keep warm. I have heard moans, screams, and sounds I frankly don’t know how to describe. Cancer wards have been called houses of horror. I wish I could dispute the characterization.

I’m also still afraid of leaving Oscar and my daughter, A.J., without a father. Not because I don’t think they’ll be okay. I have an abiding faith in them. But if there is anything hard-wired into parents of the human species, it is to provide for their offspring. To be unable to do that, even if that inability is beyond my control, would be, to me, an unforgivable failure.

I’d also like to see A.J. and Oscar grow up, start their careers, and get married and have kids if they choose to. I’d like to spend my retirement with Didi, write more, fish more, play more poker, and go on more trips with family and friends.

I don’t fear being dead. I fear not being alive.

The DCEP was supposed to be a lion. Physically, at least, it was a lamb. The lymphodepletion was supposed to be a lamb. It turned out to have a bite.

My treatments were scheduled for a Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Sunday was left open as a rest day. Monday I would check in to the hospital for my CAR-T.

Like DCEP, lymphodepletion is administered by IV, but on an outpatient basis. After my first infusion, I felt okay. After the second, I felt lousy. After the third, I felt as sick as I’ve been from any cancer treatment I’ve had. I was nauseous, dizzy, and so weak I could barely drink a glass of water or get out of bed. I had to crawl on all fours to go to the bathroom.

For better or worse, humans tend to regard a full head of hair as a sign of good health and losing one’s hair as a telltale sign of cancer. I’ve always had a good head of hair. As an adult, I’ve tended to wear it long on top and short on the sides, with one piece dangling over my forehead. Didi calls it my Superman curl.

Although my hair had begun to fall out somewhat during the DCEP, it now fell out completely. When I showered, the shampoo lather in my hands was flecked with thousands of little pieces of black and gray stubble.

That was more upsetting than I thought it would be. My attempt to preempt that feeling by getting a buzz cut didn’t really work—some things you can’t prepare for. After almost twenty years, I had finally experienced perhaps the most familiar side effect of having cancer. Losing my hair was an unmistakable and undeniable sign of my illness, and it stung. The Superman curl was gone.

After my final lymphodepletion treatment, I took a cab home from the hospital. It was Saturday, June 24, 2023, the day before the New York City Pride March, and because several major streets had already been blocked off, the traffic was gridlocked. A ride that might normally take forty-five minutes had already taken well over an hour, and I still had more than twenty blocks to go.

As we inched along Park Avenue South, a pickup truck pulled up alongside my cab. It was a red Ford F-150 with New Jersey plates. The driver and front-seat passenger were young men in their early twenties, wearing tank-tops and baseball caps. Bon Jovi was blasting from their speakers. If they were characters in a movie, you would have dismissed them as too on-the-nose.

In preparation for losing my hair during the two rounds of chemotherapy, I got a buzz cut.

As one does when one is in the middle of having one’s immune system wiped out in preparation for a futuristic cancer treatment, I was wearing a mask in the backseat of the cab and had my window down. The driver of the pickup, who was now no more than a few feet from me in the lane to my right, also had his window open. Even before he spoke, I knew what he was going to say.

The exact quote was, “Dude, lose the mask.” His wingman laughed.

In my family, we like to tell a story about my father. When I was maybe five years old, all six of us, my father, my mother, my three siblings, and I, were skiing in upstate New York. It was a particularly crowded day and there was a long line for one of the lifts.

When a group of teenagers tried to skip to the front, my father, who was a famously gentle soul but also someone who believed in rules, called them out.

“Sorry, guys,” he said. “We’ve all been waiting here a long time. You’ve got to go to the back of the line.”

The kids ignored him.

“Guys, go to the back.”

Nothing.

“Guys …”

And then: “Fuck you, old man.”

That was it. Something inside my normally mild-mannered father snapped. He popped his boots out of his skis, walked over to the kids, and grabbed the leader of the pack by his coat lapels.

“Go to the back,” he said. “Now!”

And to the back they went.

Back on Park Avenue South, I channeled my inner Gene Gluck.

I got out of the cab (the traffic was stopped anyway) and walked up to the pickup truck driver.

My midstreet soliloquy went something like this: “I’m a cancer patient, asshole. I am on my way home from a chemotherapy appointment. On Monday, I’m going into the hospital for two weeks of a treatment that could kill me. I’m wearing a mask because my immune system doesn’t work. Fuck you.”

In terms of the power of my performance, it didn’t hurt that, thanks to the DCEP and lymphodepletion, I hadn’t just lost most of my hair, but I was also thin and ashen looking.

In fairness, the second I stepped out of the cab, the driver seemed to sense what was happening, and once I confirmed his suspicion, he seemed genuinely remorseful.

“Sorry, dude,” he said. “My bad.”

I got back in the cab and he and his sidekick turned right at the next cross street, I suspect to avoid having to inch along next to me any longer.

I usually don’t believe in playing the cancer card. In most situations, it’s too powerful a tool for the job, not to mention manipulative. But on that day, I made an exception.

On Monday, June 26, I checked into Mount Sinai again, this time to receive my CAR-T treatment. The doctors and nurses explained to Didi and me that the infusion itself would be painless and only take half an hour or so.

After that, they would carefully monitor me—at first every fifteen minutes, then every half an hour, then every hour, and several times a day after that—for symptoms of CRS and neurotoxicity for the duration of my two-week hospital stay.

The CRS monitoring would involve blood tests and temperature and blood-pressure checks. The neurotoxicity screening would entail asking me if I knew my name, what day it was, what city I was in, and so on, and handwriting tests to track my motor skills.

As we had been told before, I would be allowed only a limited number of visitors, and everyone was required to wear a mask. I came equipped with two novels, three books of crossword puzzles, and my Netflix, Hulu, and Peacock subscriptions. My sisters and brother sent me a picture of the four of us from a family wedding to keep by my bedside.

I planned to work while I was in the hospital. Dr. Richard supported it. It would help me keep my mind off of things, she said. To keep Zoom meetings from being creepy, I would either keep my camera off or customize my background to something other than a hospital room.

When the time came, one of the nurses wheeled in an IV pole with the bag containing my CAR-T cells hanging from it. The fluid in the bag was colorless and generally unremarkable, like so much water. I remember wondering how something so extraordinary could look so plain.

Then the nurse took the plastic line running from the bag and attached it to the catheter that had been placed in my chest earlier in the day. I watched the first few drops dangle from the valve at the bottom of the IV bag, then break loose and travel down the line into my veins.

Didi was sitting next to my bed, in the visitor’s chair.

“Okay, cells,” she said. “Work.”

For the first few days of my hospital stay, I felt fine. Not that I was having the time of my life or anything. The temperature checks, blood-pressure checks, blood draws, and cognitive-function tests were incessant.

“Are you in any pain?”

“No.”

“I’m going to take your blood pressure now.”

“Okay.”

“And now your temperature.”

“Sure.”

And so on.

I’ve been stuck with needles hundreds of times. I’m used to it. But being awakened every night at midnight and 3 a.m. to get jabbed was new to me.

Showering was a Catch-22. Because of the catheter, I wasn’t allowed to take a standard shower because I could develop an infection, but because of my compromised immunity, I needed to keep my skin clean to avoid infections. The prescribed solution was a special kind of disinfecting wipes that are safe to use every day on your skin. I can report they are a poor replacement for a shower.

For the cognitive tests, one of the doctors or nurses would ask me to write “my sentence,” a copy of a sentence they had me write on the first day as a baseline so they could monitor my fine motor skills. My sentence was, “Today I ate breakfast, watched TV, read a book, and took a walk down the hallway.” Shakespeare!

Then a doctor or nurse would ask me a series of questions.

“What’s your name?”

“Jonathan Gluck.”

“Where are you?”

“Mount Sinai Hospital.”

“In what city?”

“New York.”

“How old are you?”

“Fifty-eight.”

“What is that?” [Pointing to the television.]

“A television.”

Etc.

Finally, they would ask me to raise my right hand, touch my finger to my nose, or some such.

On the third or fourth day, when one of the nurses asked me to raise my hand, I didn’t immediately do so.

She paused.

“Are you okay, Jonathan?” she asked.

“You didn’t say, ‘Simon says,’” I said.

For the record, she laughed.

Boredom was another issue.

To pass the time, I binge watched season two of The Bear. (Excellent). I read two books written by former colleagues (Bad Summer People, by Emma Rosenblum, and The Eden Test, by Adam Sternbergh). I finished three compilations of New York Times crossword puzzles (my crossword game was never stronger). And I watched literally every minute of the Tour de France, more than eighty hours of televised bicycle racing. (Check out Jonas Vingegaard’s thrilling Stage 16 time-trial win, in which he deals a decisive blow to longtime rival Tadej Pogačar, on YouTube.) Because watching sports on TV has always been a kind of Prozac for me, I threw in a few dozen Wimbledon matches (delighted for Carlos Alcaraz, sad for Ons Jabeur), the women’s U.S. Open golf tournament (congratulations to first-time major winner Allisen Corpuz), and a nightly dose of Yankees and Mets games (all equally and pleasantly boring) for good measure. Regarding the question of whether I watched a cornhole tournament on ESPN, I plead the fifth. (Go, Jamie Graham!)

If you are sensing a theme of escapism, you are not wrong. During my hospital stay for my DCEP treatment, I had read Endurance, Alfred Lansing’s account of the ill-fated Shackleton expedition. I thought the epic story of survival might inspire me (at least I wasn’t stranded on an Antarctic ice floe eating seal blubber to survive), and to some extent it did. But it was also maybe a little too intense. My own saga, I decided, was harrowing enough.

I will spare you my complaints about hospital food. Actually, I won’t. But I will limit them to the coffee. The coffee was horrible. Ghastly. Arguably evil. In fact, I hesitate to dignify it by calling it coffee. It was instant Nescafé, the kind they package in those skinny little packets to make them look European, dumped into a Styrofoam cupful of lukewarm water. You know the little puddles that form on the side of the road after a rainstorm, the ones with the rainbow-colored oil slicks on their surface? The coffee didn’t taste like that; it tasted worse. Have you ever forgotten to change the water filter under your kitchen sink for three years, until the filter is so saturated with dirt and bacteria it could qualify as a Superfund site? Imagine wringing out that filter and drinking the afterproduct. Then account for the fact that the coffee tasted ten times as bad.

Put it this way. On Day Four, I began sneaking down to the Starbucks in the hospital lobby, despite the infection risk that posed, to get my caffeine fix. In other words, the hospital coffee was so bad I risked my life not to drink it.

On the bright side, because I was now severely immunocompromised, I was assigned a single room. That meant I had many hours to myself. Didi has confided in me that she sometimes likes to go on business trips because staying in a hotel room by herself offers her a rare escape from the demands of me, the kids, the cats, and everything else. It’s precious alone time. That thought may or may not have crossed my mind.

One morning, when I was heading back to my room after getting coffee in the lobby, I came across a yellow sticky note placed next to the Up and Down buttons on an elevator.

It read: “Every day above earth is a Good Day! Xoxo.”

To the person who wrote that note, I say, “Amen.”

Discharge day was Tuesday, July 11. I had a final check-in (“Are you in any pain?”), my catheter was removed, and I was free to go.

Didi had brought a bag full of makeup, nail polish, and face creams as a thank you gift for the nursing staff. We left it with the chief nurse and headed straight for the exits, as they say on the hospital TV shows, stat.

On our way to the elevators, I ran into a woman I’ll call Barbara. Barbara was a fellow CAR-T patient and one of the hall walkers. Scratch that. She was the hall walker. She was out there every day, marching back and forth, for an hour or longer, at a clip at least triple that of any of the rest of us. She was maybe sixty-five years old and had a strong, calm air about her. It seemed to say, “I am aware of your power, cancer. But I’m sorry, you will not defeat me.”

It was obvious I was leaving; I had my suitcase with me.

Previously, Barbara and I had chatted a few times and exchanged small talk. But at that moment, we didn’t need to speak. We understood each other perfectly, almost telepathically. What each of us was saying to the other was, “I’m sorry. I understand. Good luck.”

Adapted from An Exercise in Uncertainty, Harmony Books 2025

esquire