My High-Tech Wellness Journey Through South Korea

Would you be surprised to learn that only three percent of US health care is spent on preventative care? Even in today's political climate, that seems drastically low. It's a staggering fact that Dr. Hon Pak, Senior Vice President and Head of Digital Health Team at Samsung US told me when I visited the mega brand's Digital City campus, in the heart of Suwon, South Korea. This really opened up my eyes as to why tech companies are investing more than in the future of health and wellness more than ever.

My journey began a few months ago when I headed to South Korea to learn how Samsung gadgets are becoming the vital middlemen between patients and doctors, and how apps are the facilitators. That’s the vision for the future of Samsung Health, and it’s based on some shocking data.

By and large, Americans keep chugging along until an ailment forces them to stop, even when the red flags and warning signs are at their very fingertips. Wearables like smartwatches and fitness bands can help bridge this by doing what this tech is already good at—detecting patterns and suggesting changes—and making it better. Here's what I learned on my journey filled with wearables and the newest tech—it's the most informative trip I've been on to date.

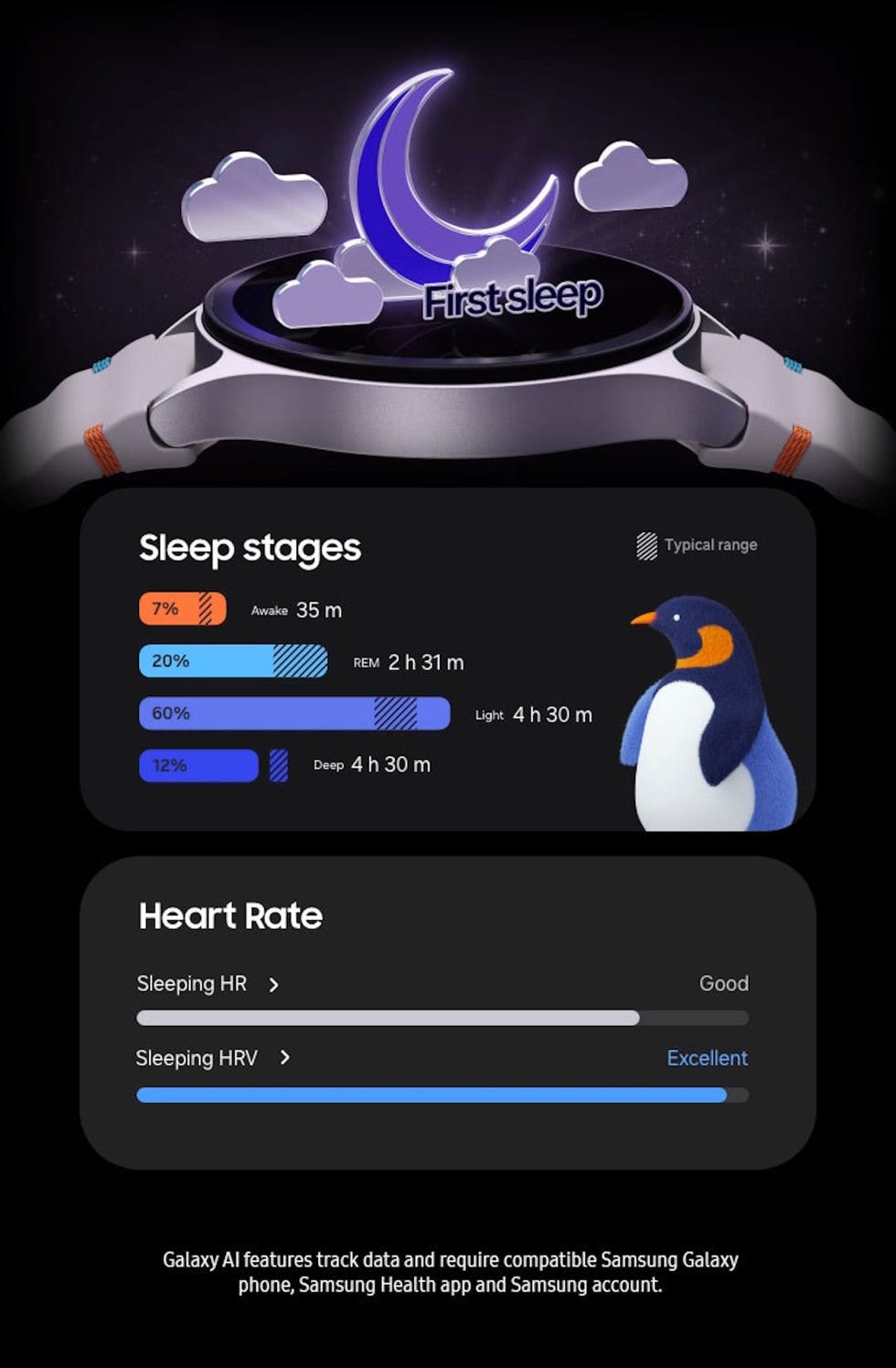

Traveling across the world doesn't come without fatigue. A 13-hour time difference on a continent I’d never visited hit me harder than I expect. During this time, I used the Galaxy Watch to get a sleep tracking baseline before my trip. For what it’s worth, I much preferred sleeping in my own Galaxy Ring. Both integrated with the app and together corroborated one indisputable fact—I am an excellent sleeper.

The Health app tracks your sleep habits and—based on sleep time, consistency, and waking during the night—uses AI to determine which of the eight “sleep animals” fits you best. As it turns out I am an Unconcerned Lion, the best there is at getting eight hours of undisturbed sleep per night. If you’re an American, you’re most likely a Nervous Penguin, which means you have good sleep time and consistency but wake periodically throughout the night. The Penguin is a Tier 2 animal, nailing two of the three core pillars of sleep. Tier 3 includes Sensitive Hedgehogs and Cautious Deer, sleepers that only check one of the three boxes.

After a week, you can begin a personalized AI Sleep Coaching program that will address the specific bad bed time habits it identified, offering up suggestions like adjusting room temperature. More detailed opt-in features include sleep apnea risk and snore detection (yes, this one is real and it works great). All great stuff, but nothing I could make use of on five hours of tossing and turning—which is how I slept my first two nights in Seoul.

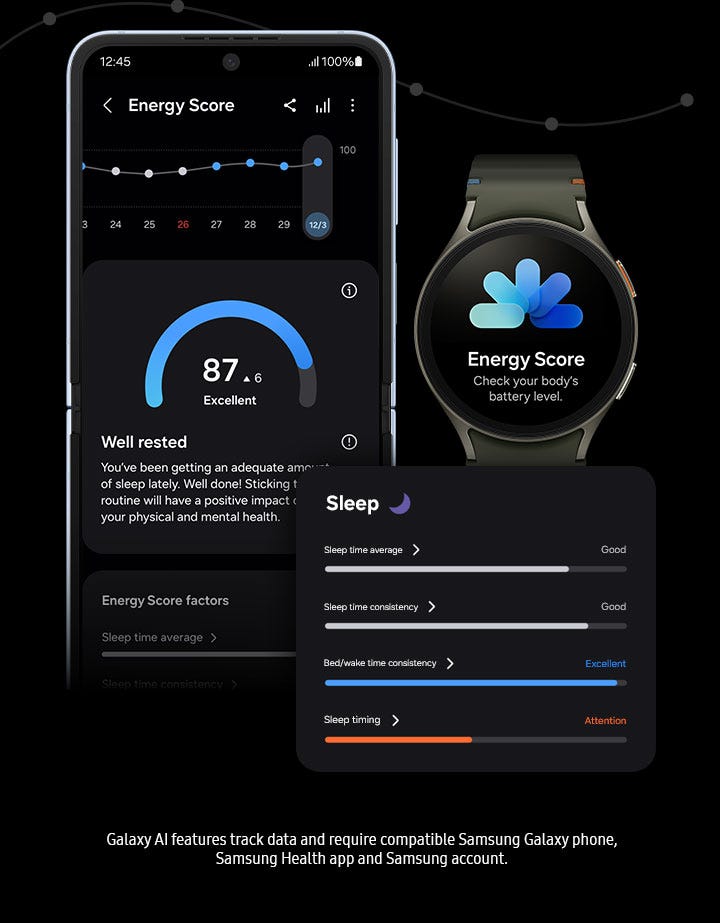

But as my body adjusted to the time difference over the week, commuting between Seoul and Suwon, my sleep improved with it. Using new Health features including Bedtime Guidance—which uses your past three nights of sleep data to determine your optimal bedtime— I settled into a new routine. Others, like Antioxidant Index, reminded me to ditch the “just coffee” breakfasts and eat a fruit and veggie every now and then.

As we trekked through Seoul, we were encouraged to check in on our blood oxygen and stress levels on our Galaxy Watches. Stress is based on heart rate variability (HRV) and when it starts to fluctuate your watch will send you suggestions to "take it easy."

I couldn’t help but feel silly sleepwalking through Gangnam at 8pm, ignoring the push notifications telling me to take the day off, when I knew tomorrow was going to be another day of exceeding my step count before lunch. It made sense, given Samsung Health’s gamified approach, that it wouldn’t want me to continue to push myself and get an injury. But it mostly spoke to the disconnect between our bodies and our devices that still exists. How can we be expected to change our behavior based on suggestions that lack human context? There’s no way of telling my watch “this might be the only time I see Seoul in my entire life, dummy.”

To its credit, the app does base scores and suggestions not just on the last night of sleep, but on the previous two before it. Still, it wasn’t enough to account for how much of five days of international travel, at least 26 of those hours spent on an airplane, is mental. I was exhausted every day in Seoul and the app and my low scores reflected that—but I felt fine every morning. Raring to go, even. My body knew, instinctively, how to bank that sleep debt and balance out the deprivation with adrenaline. And it didn’t need an app to tell it to sleep all weekend once I arrived back home and the jet lag caught up with me. Debt repaid.

The Human BarrierIn the month that’s passed, I have continued to track myself with Samsung Health. My sleep has returned to Lion status, but in terms of general health I’ve fallen back into patterns. I have been making more of a point to exercise multiple times a week, but mostly falling short. It’s not just Samsung’s ecosystem. I’ve tried all the others too, Whoop, Oura, etc. If big tech wants health tracking to become the front-line of healthcare, they all have yet to overcome the same thing, the human barrier.

The reason health apps are designed the way they are is because we're stubborn beasts of routine. It's easy for me to fall back into habits like drinking, eating fast food, and biting my nails because, honestly, they feel good. Sending notifications and health checks to your watch or phone are the way these apps activate your brain's dopamine and become part of your routine. In a perfect world, a push notification from your smart watch helps you make positive changes. But information can only go so far to enable action, especially in an era of information overload. If this is the future tech companies believe in—and really, the future is already here—the onus will truly be on the individual to take care of themself.

To Samsung’s credit, the U.S. market represents a singular uphill battle: caustic individualism and unaffordable healthcare. The technology is here, and if suggestions are followed, it can markedly improve your life. But if health tracking is to become the first line of defense, it needs to become accessible and there needs to be an incentive to adopt it. Smartphones have fully proliferated society, proving that accessibility comes with time; the wearables attached to them might take a few years to drop in price and build a robust secondhand market, but it will happen.

If a Samsung wearable could get you insurance reimbursement, the same way a dashcam does for car insurance, I think units would sell out pretty quick. The tech has arrived. The next step is the incentive.

esquire