Donald Trump, Mike Tyson, and the Fight That Defined an Era

There may have been, in the long and sordid history of boxing, a more perfidious lead‑up to a big fight. But never before—or since, for that matter—had the treacheries been so blatant, been made so public, and been so deeply rooted in the personal life of one fighter. For all the mournful blather wishing for just boxing, it was the treasons themselves that made the fight between Mike Tyson and Michael Spinks on June 27, 1988, the most hotly anticipated fight since Ali–Frazier I. The difference was Ali–Frazier had been an almost even‑money proposition. The odds for Tyson–Spinks, while narrowing, had opened with Tyson a prohibitive 5–1 favorite.

Still, people couldn’t get enough. The shit in the champion’s life had become addictive, a global jones nourished each morning amid the acrid scent of newspaper ink: his wife, the fetching Robin Givens, and her tennis pro sister, depicting him a violent boozer just a week out from what was being billed as the “Fight of the Century,” claiming that Tyson’s embattled manager, Bill Cayton, had sicced a squadron of private detectives on her and her mother, trying to engineer her divorce from Mike. Meanwhile, Don King—not merely the world’s greatest promoter, but also its most Machiavellian—was scheming to depose Cayton and gain control of the most lucrative prize in sports. It’s not difficult to imagine the week in Tyson’s life as a B movie, complete with spinning headlines:

"Iron Mike’s Fighting Mad""Charge Tyson KO’d Wife""Mom‑in‑Law Says She Fears for Life""King: Cayton Sought to Bribe Priest""Rival King Says Cayton Is a “Satan in Disguise”"

"Tyson Star (Victim?) of a Real Soap Opera"

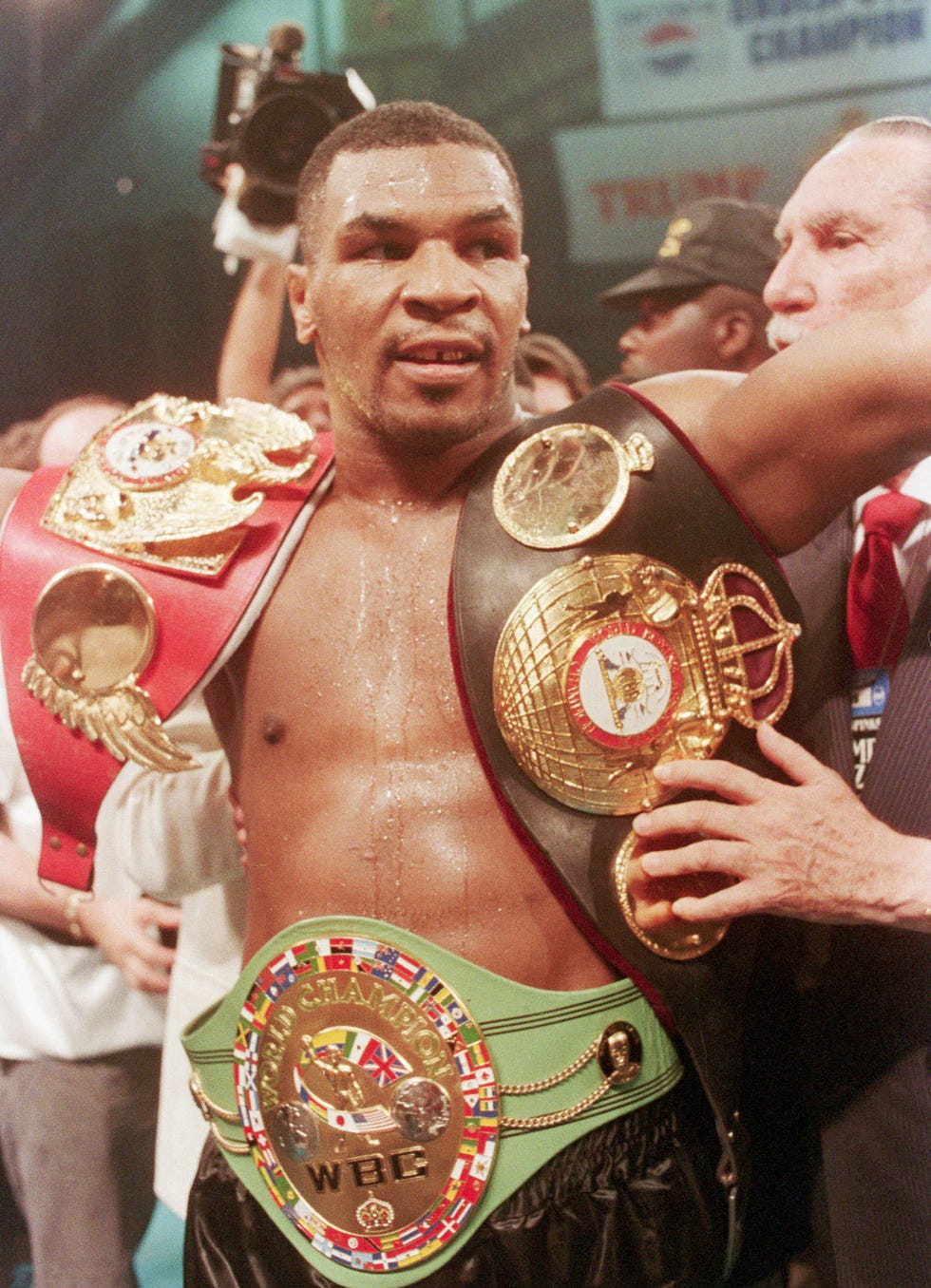

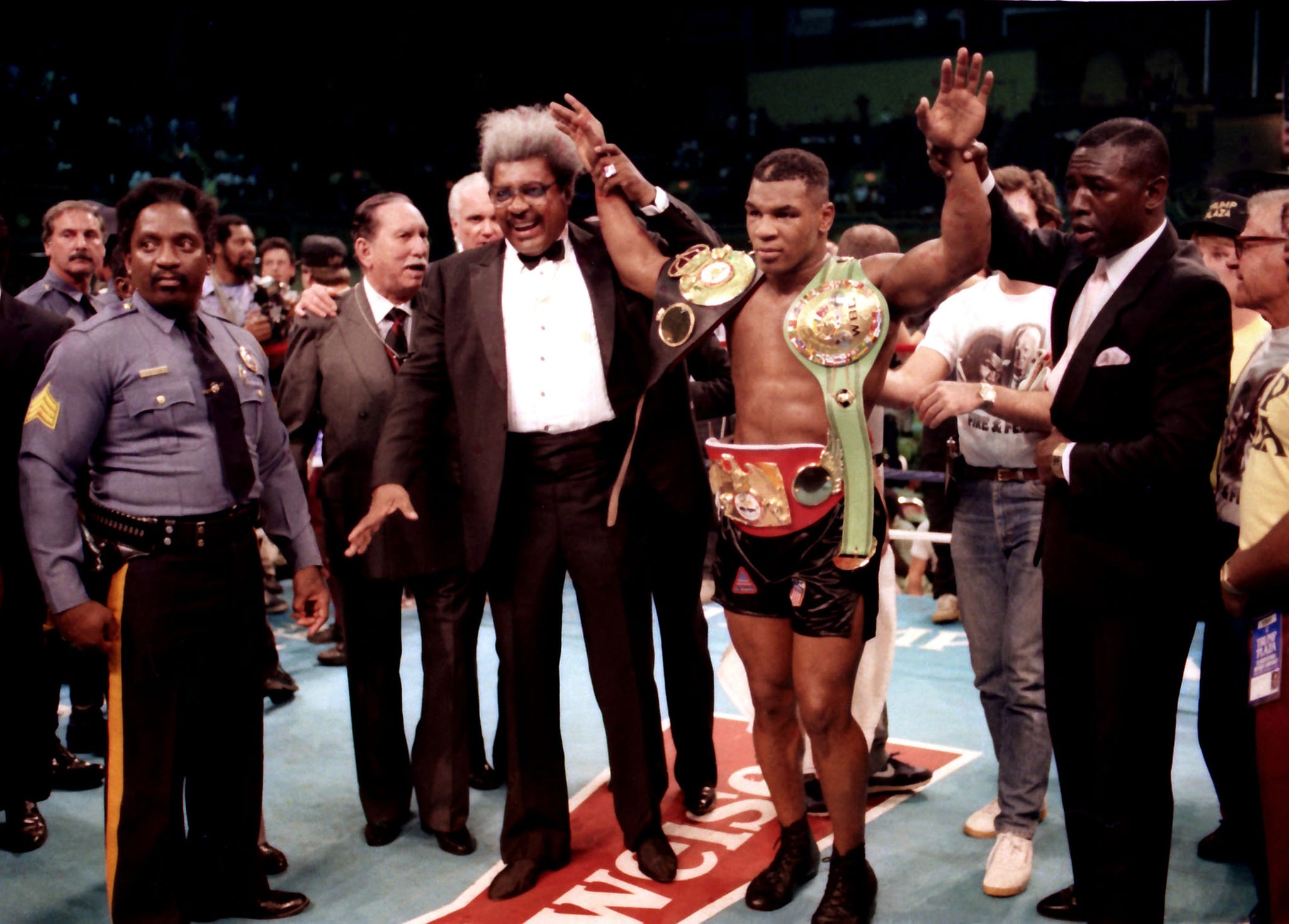

Tyson, draped with his three heavyweight champion belts, after knocking out Michael Spinks, June 27, 1988, in Atlantic City.

Still just 21, Tyson was bigger—way bigger, in fact—than Michael Jordan. He made more money than television’s highest paid performers, Bill Cosby and Oprah Winfrey. But now he found himself at the precipice of something else, a cultural moment. Just as the Roaring Twenties are said to have begun with Jack Dempsey’s destruction of Jess Willard (seven knockdowns in the first round alone) in 1919, so can one argue that the nineties—christened “the Tabloid Decade”—began in 1988 with Tyson–Spinks. The coin of the realm in Tabloid America was celebrity. A Trump Plaza press release, listing no fewer than fifty boldface attendees, concludes with this rhetorical gem: “Which one of the aforementioned celebrities gets the best seat?”

Why, the future president himself, of course, whose rumored dalliance with the champion’s bride, fictitious or not, was already making its way through the press room.

The least famous person in this entire mix was the challenger, Michael Spinks. Tyson regarded him as just another guy. All he had to offer on the subject was a variation of what he’d told Sports Illustrated before his TKO of Tony Tubbs a few months before: “I’ll break Spinks.”

An Olympic gold medalist back in ’76, Spinks had made a career of beating both bullies and long odds. He’d made it out of Saint Louis’s Pruitt–Igoe projects and made boxing history by beating Larry Holmes ending Holmes’s bid to beat Rocky Marciano’s record of 49‑0 and becoming the first light heavyweight to win the heavyweight title. In the years since, Spinks had beaten Holmes in a rematch and knocked out Gerry Cooney. He was awkward, undefeated, and conspicuously modest, with a curiously potent right hand, the “Spinks jinx.” At 31‑0, just a couple weeks shy of his thirty‑second birthday, Spinks was very much unlike Tyson—a grown man both physically and emotionally. “I’ve never run from anybody,” he deadpanned at the final pre-fight press conference.

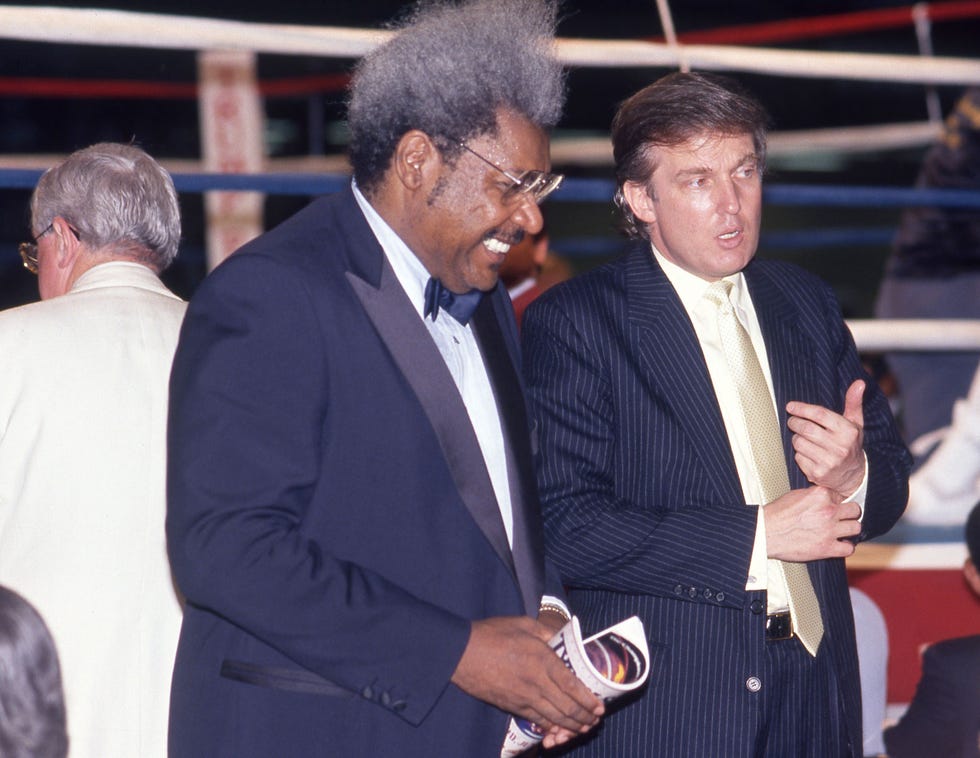

Don King, the notorious boxing promoter who championed the fight, and then-real estate mogul Donald Trump, who hosted the fight at the Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, arrive.

Tyson’s suite in the Ocean Club had been decorated with a vast array of sepia‑toned photographs featuring the all‑time greats. Among them was Stanley Ketchel, who moved John Lardner to write his famous lede: “Stanley Ketchel was 24 years old when he was fatally shot in the back by the common‑law husband of the lady who was cooking his breakfast.”

One could easily imagine such a fate, or worse, for Tyson. Never had a kid been so explicitly warned about the mistakes that fighters make, and yet none seemed so doomed to repeat every damn one. Then again, none of Tyson’s predecessors ever had the dysfunctional pieces of his interior life so ruthlessly exposed and examined on the eve of his biggest moment.

Tyson began to sob. “I wanted to make him happy,” he said of his trainer and savior, Cus D'Amato.

Consider him just several weeks prior: running in the 4:00 a.m. darkness along the boardwalk of a dilapidated carnival city.

“I can hear his voice,” Tyson would remark some hours later.

It was the voice of Cus D’Amato, his ghost and savior, the eccentric trainer who’d liberated him from juvenile lockup at 13. An audience of three reporters had been granted an audience after the morning workout. Tyson didn’t know them too well, but the oldest one, Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star‑Ledger, knew D’Amato—dead less than three years now—from the old days. He was choking back tears. First, he began to cry, then sob uncontrollably.

“I wanted to make him happy.”

It’s said that a happy warrior is a dangerous one. But this kid was joyless.

“There’s nobody to trust.”

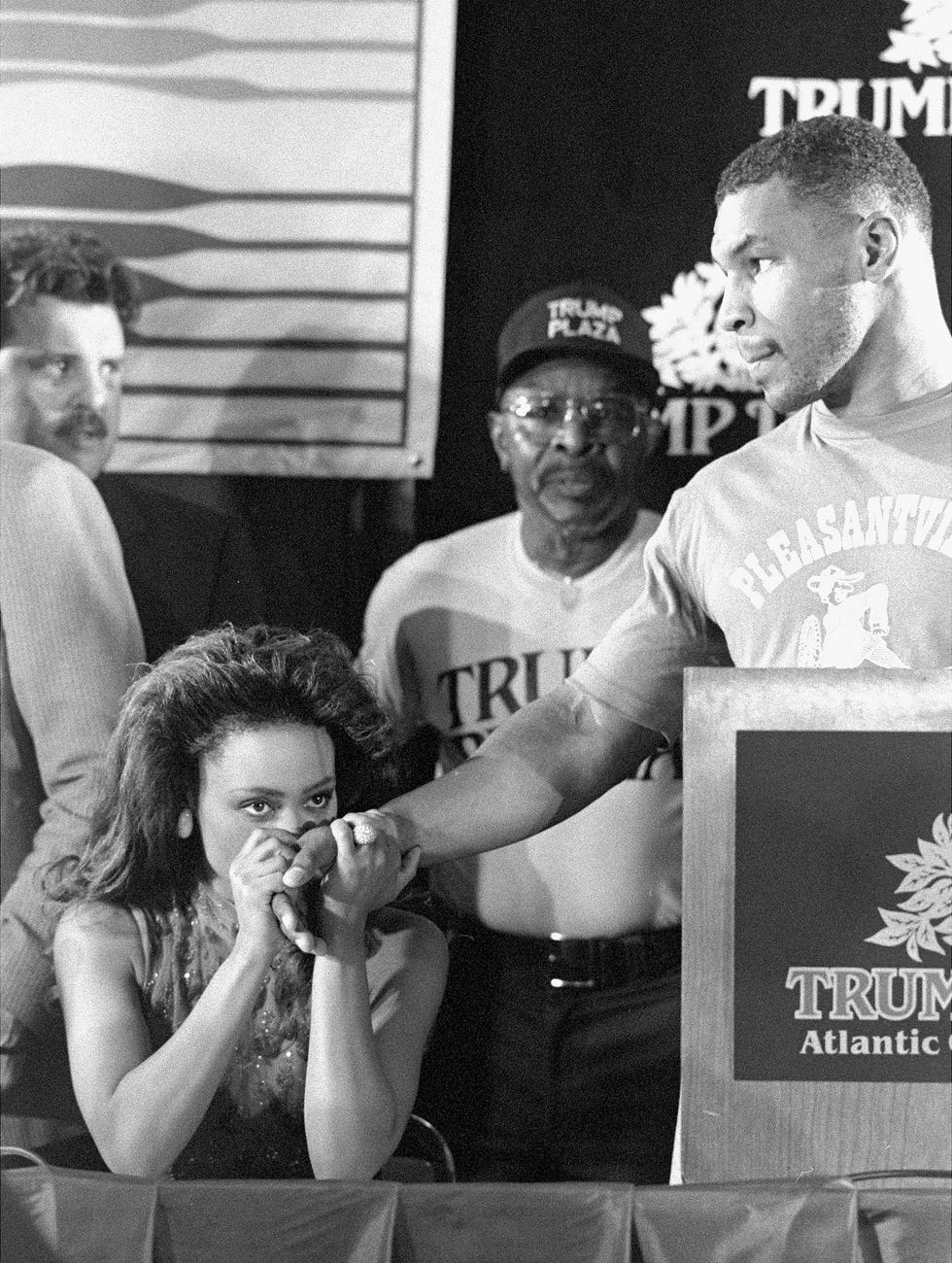

At the post-fight press conference, a murderers row: From left, legendary fighter Roberto Duran, who gave pre-fight advice to Tyson; Tyson; Tyson’s wife, Robin Givens, resplendent in red; trainer Kevin Rooney; and promoter Don King.

For all the talk about taking Spinks’ manhood Tyson’s shadow self remained: confused, vulnerable, alone, and not that difficult to find. One can argue, quite reasonably, that he faced Spinks in the midst of a breakdown.

From the writer Pete Hamill’s notes at the weigh‑in, the day before the fight:

In his last workouts T looked ragged, without fire. T is a kid, his emotions close to the surface.

I’ve known fighters who lost fights in order to know who their friends were.

I’ve known wives who wanted their husbands to lose to bring them down to earth.

Spinks lost wife in a car accident and two months later defended his championship brilliantly. Ali changed wives right before the Thrilla in Manila. Ray Robinson fought with grace and power and discipline no matter how complicated his domestic relations.

Others have been wrecked . . .

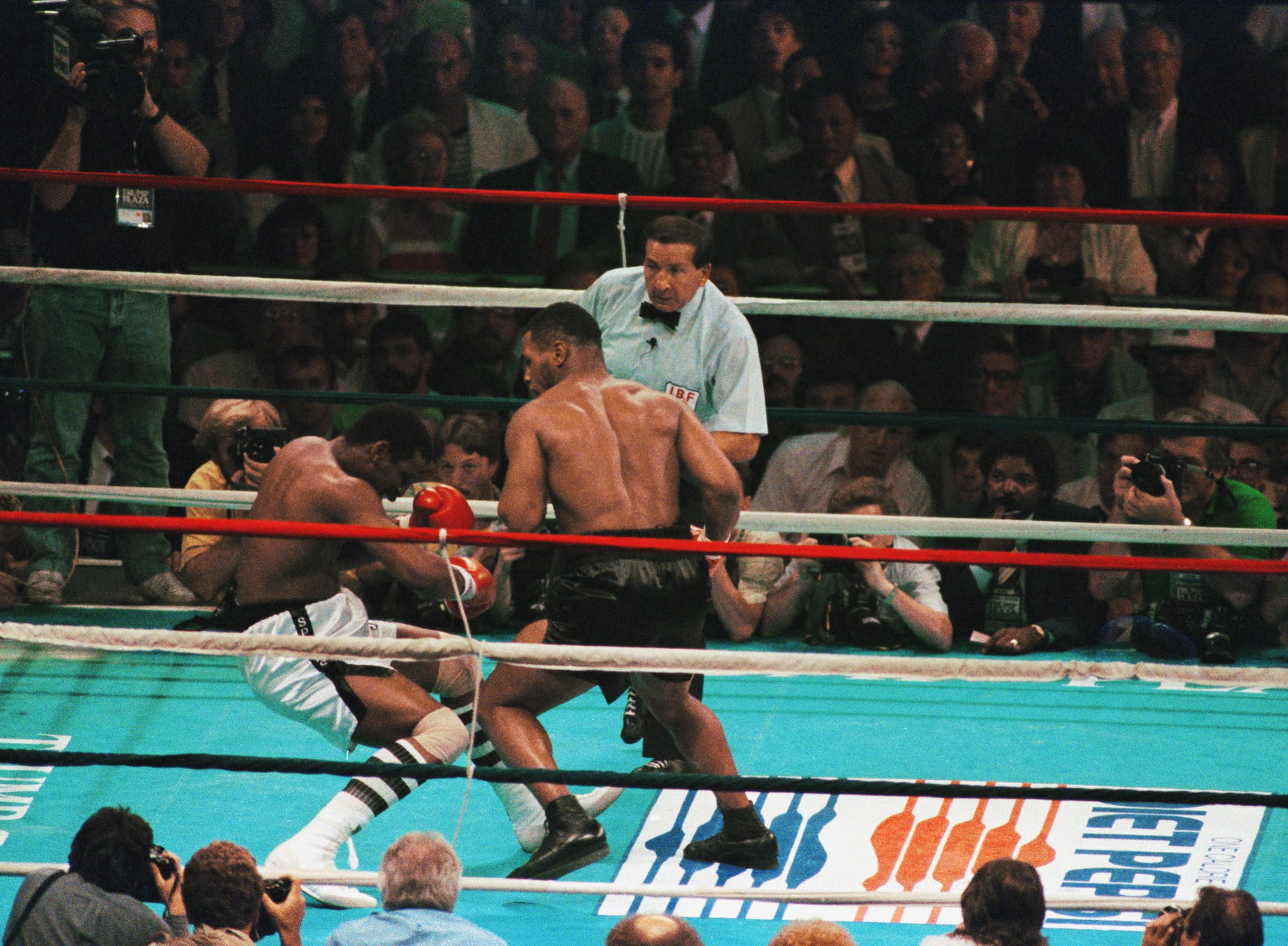

Spinks recoils from Tyson’s knockout punch.

Fight day begins with Donald Trump in the ring at the convention center. He’s congratulating himself on Good Morning America. “It turned out to be much bigger than I even thought,” he says. “This has turned out to be gigantic.”

Not to be outdone in her own GMA segment, Robin—who predicts her husband’s winning by knockout in the fourth—calls Tyson–Spinks “the biggest sporting event of the century.” When asked about the salacious coverage, and the depiction of her as a gold digger, she tells the host, Spencer Christian, “I think it helps sell tickets and unfortunately, it’s at our expense.”

On the bright side, however: “It has made us so much closer.”

So close that years later she will write: “The day of the Spinks fight we must have made love for hours.”

Ringside tickets have a face value of $1,500, a record, of course, though Trump himself had to be talked out of charging $2,000 (about $5,400 today)—apropos for a fight that one Washington Post columnist has deemed “a monument to a decade of greed.”

Trump will throw a presser at his hotel and casino, graciously volunteering to be Tyson’s “advisor.”

The fight will set many records, all of them measured in dollars: a $12.3 million live gate (eclipsing the previous record, $6.8 million for Hagler–Leonard the year before), a Trump Plaza pit drop of $11.5 mil‑ lion, $27 million from closed‑circuit, and an unexpected $21 million windfall from six hundred thousand cable subscribers willing to shell out $35 a pop for the pay‑per‑view. “Closed‑circuit is the way of the past,” the dealmaker and promoter Shelly Finkel declares at the final presser, promising “the largest‑grossing, largest‑netting fight in history.”

Flush with success, Finkel has gotten a call from Robin’s mother, Ruth Roper. “I made a mistake,” she confides. “I let the fox in the hen house. And now I can’t get him out.”

King, she means. She’s coming to realize there’s a price for having allied herself with King against Cayton.

King is everywhere, milling about at the prefight VIP party, for which 1,200 pounds of lobster tails have been delivered, along with the endless jeroboams of Dom Pérignon. King is with Herschel Walker, then getting a hug for old time’s sake from Norman Mailer, and next posing for a photographer with Trump, Jackson, and Malcolm Forbes, who’s holding a crumpled dollar bill, a gift from Jackson, who wanted to say the capitalist shaman owed him money.

Even Cayton makes an appearance. Trump puts his arm around him. “Bill,” he says, “I’m with you one hundred percent.”

Trump, whom Cayton listed as a reference on the application for his manager’s license, is about to fuck him, of course. In a matter of days—after Roper’s lawyer sues Cayton on Tyson’s behalf—Trump will announce his own alliance with Robin and Ruth. He’ll throw a presser at the Plaza, and graciously volunteer his services as Tyson’s “adviser.” He’ll make it clear how Tyson “respects” him, and that his end of their arrangement, nothing for personal gain, but all go to charity—AIDS, cerebral palsy, MS, and homelessness.

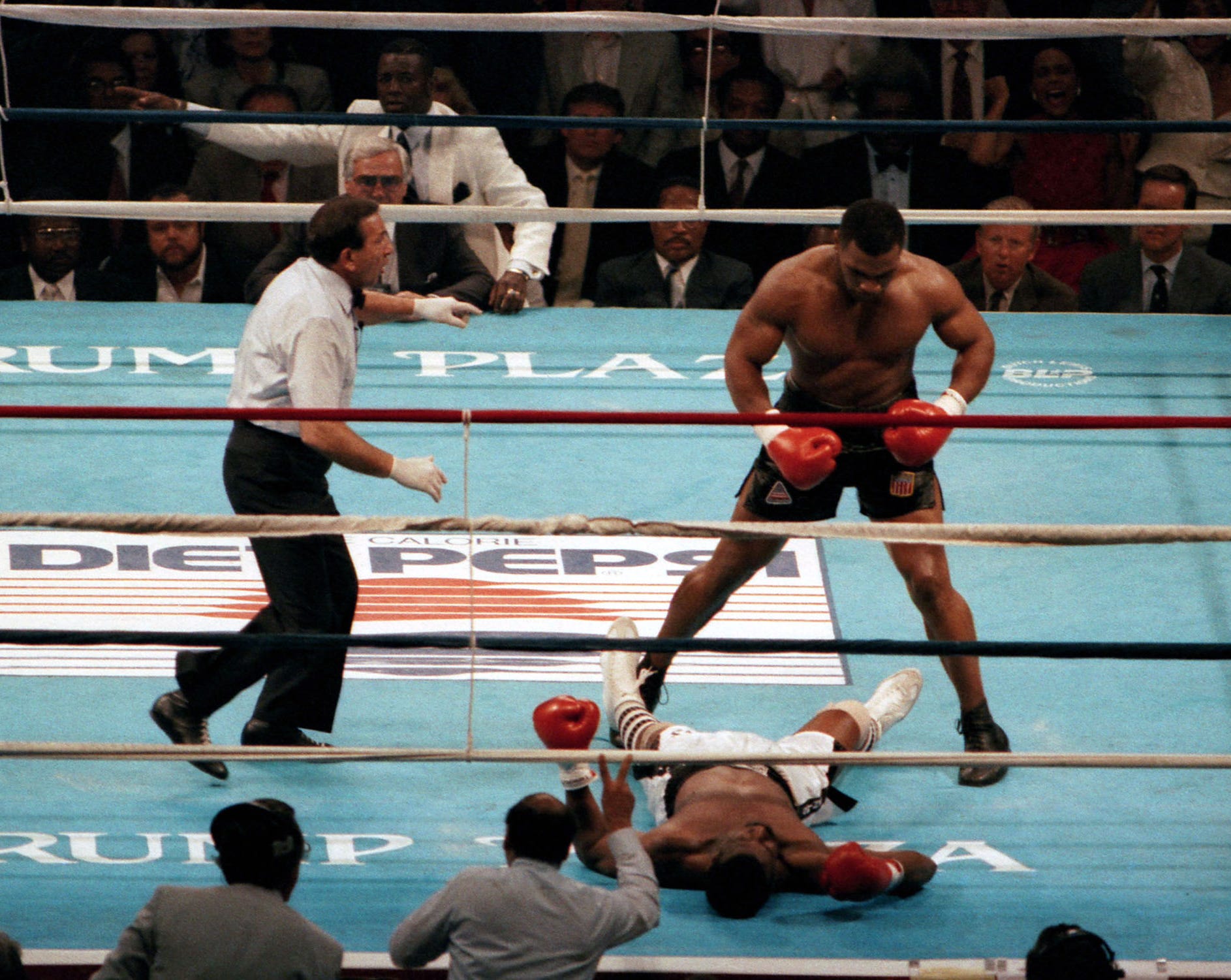

Tyson awaits referee Frank Cappuccino’s count as Spinks is down.

Atlantic City came of age with the Miss America pageant. But now the city has, in the words of one correspondent, the look of “decayed teeth.” Its pawnshops bear signs promising CASH FOR FOOD STAMPS, GOLD. Nevertheless, scalpers are getting up to five grand for a ringside seat. By the West Hall entrance, Hamill counts a line of thirty‑seven limousines, along with a tour bus and an ambulance. Inside, there’s a row of eight Japanese guys in the third row who could pass for yakuza.

Norman Mailer, now sixty‑five, is there for Spin magazine and recalls, in this very building, with its dismal armory‑style architecture, the 1964 Democratic Convention and the giant photographs of the nominee, Lyndon Johnson, that hung behind the podium. A convention is, like Miss America, just another pageant, though, and so is a title fight. Instead of red, white, and blue bunting, this one’s festooned with Diet Pepsi logos. It’s gloriously packed—official attendance 21,785.

“When I see Don King,” Larry Holmes tells a journalist, “I see the devil.”

The celebrity introductions—featuring such boxing luminaries as Carl Icahn and Laurence Tisch—are endless. Jesse Jackson is introduced as “a friend of Donald Trump.” All that makes it tolerable are the boos. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner gets the very worst of them. Sean Penn, scowling throughout in his Izod polo, is also roundly jeered; his wife, Madonna, less so. Detroit Pistons center Bill Laimbeer is lustily booed—as is the ever‑undeterred Don King.

“When I see Don,” Larry Holmes tells Newfield, “I see the devil.”

The operators: King and Trump.

Now there’s been a delay. “Moments ago, in the dressing rooms, a major controversy erupted,” booms Jim Lampley, as the broadcast cuts to a man in a white tux, no shirt, met by a phalanx of cops outside Ty‑ son’s quarters. “You’re looking at a taped shot of Butch Lewis, the manager of Michael Spinks, who went wild after he discovered that Mike Tyson had had his hands taped and, apparently, had the gloves put on without a representative of Spinks’ camp being in Tyson’s dressing room.”

Soon the cameras are following Larry Hazzard, chairman of the New Jersey commission, on his way to the dressing rooms. Hazzard understands Butch is trying to poke the bear, hoping Tyson will unravel. He can also see what the now‑enraged Tyson has done to the wall.

“Put his hand right through the fuckin’ Sheetrock,” says Hazzard.

Finally, Hazzard gets Eddie Futch from Spinks’ dressing room. “It’s fine,” says Futch, who by now has other things to worry about.

Boxing’s reigning sage and Spinks’ trainer, now 76, Futch has studied Tyson and believes he becomes a lesser fighter after six rounds. Spinks is to stick and move, give Tyson angles until the latter part of the fight, the so‑called deep waters. Then he can drown Tyson. But Butch is in Spinks’ ear, telling him otherwise. “You go right out and crack that motherfucker,” he says. “You get your respect.”

Futch may be as good as any trainer who ever lived. But it’s Butch who convinced Spinks to leave his night shift at the Monsanto plant in order to turn pro. It’s Butch who promised he’d be a champion and Butch who got him tonight’s $13.5 million purse.

It’s Butch he believes in.

Question is, does Spinks believe in himself?

Givens kisses her husband’s famous right hand after the fight. Their tumultuous relationship was the stuff of tabloid headlines.

The broadcasters are saying that Spinks is playing games, delaying his ring entrance. But a visitor to his dressing room—the Hall of Fame trainer Emanuel Steward—notices something else. “They couldn’t even get him to come out,” Steward will recall. “He was so scared.”

In the meantime, more introductions.

At 11:04 p.m.—per the meticulous notes Hamill is keeping on a full‑page yellow pad—Jeffrey Osborne sings the national anthem.

The fans have been chanting: “Al‑ee, Al‑ee, Al‑ee.” At 11:07, their wish is granted. Ali’s wearing a blue suit with a red tie, big glasses. Don King is holding his hand.

At 11:17, Robin Givens is introduced. Her dress is a vibrant, jeweled red and matches her lips. The effect is very Dynasty. She’s booed loudly.

Finally, at 11:20, Spinks begins his ring walk. It’s a less‑than‑exuberant procession for which he has selected the single corniest tune in American popular music, Kenny Loggins’s “This Is It.”

At 11:23 the music transitions to something metallic, wordless, and foreboding. Tyson’s on the march.

Trump employees and the media surround Tyson after the KO…

With both fighters in the ring, Michael Buffer is obliged to mention just about everyone from the state athletic commission to the larcenous sanctioning bodies. Then there’s Trump. He’s orchestrated this so he can be seen with Ali.

“Ali now moved with the deliberate awesome calm of a blind man,” notes Mailer, “sobering all those who stared upon him.”

Except Trump himself, who has orchestrated this entire procession so he can be seen with Ali.

“The man who brought this great event to Atlantic City,” intones Buffer.

“Endless intro of Trump,” Hamill jots on his pad. “New Jersey thanks you, Donald Trump.”

As he leaves the ring, Ali whispers, as best he can, into Spinks’ ear.

“Stick and move,” he says. The bell rings at 11:32 p.m.

Tyson strikes first, a left hook to the top of Spinks’ head. He sees the fear in Spinks’ eyes.

Spinks fights back, though. He fires a right hand that misses. Then another.

But it doesn’t really matter. Tyson isn’t merely meaner and more re‑ lentless but also quicker and stronger.

About twenty‑two seconds in, they clinch.

As the ref, Frank Cappuccino moves in to separate the fighters, Tyson delivers an elbow to Spinks’ head.

“Hey, Mike, knock it off, man,” says Cappuccino. “Knock it off.”

With a minute gone, Tyson leaps in with a massive yet compact left hook that swivels Spinks’ head. Then a right to the body caroms off his solar plexus like a rubber‑headed mallet. Spinks drops to a knee. It’s the first time in his eleven‑year pro career that he’s been down.

“He had the look,” writes Mailer, “of a man who had just been washed overboard in a squall.”

Spinks rises, to his everlasting credit, at the count of three and assures Cappuccino he’s okay. It’s a noble deceit, but we’re down to mere ritual now. Tyson charges again. Spinks cocks his right like an archer, then lets it go, dipping as he does. The move leaves his cranium directly in line for Tyson’s counter–right uppercut, delivered like a battering ram. Spinks falls back in a heap. His head bounces on the canvas, settling just outside the ropes. His eyes look up at the lights, perhaps, or the cavernous ceiling, or, likely, nothing at

all. At the count of eight, Spinks tries to rise from a crouch. “He’s not gonna make it,” says Larry Merchant.

…not to be outdone by King, who held up the champ’s hand in victory.

Spinks tumbles, crashing into the ropes. In that moment, he’s a child capsizing on his tricycle.

The knockout is recorded at ninety‑one seconds of the first round, longer than Trump’s intro but still four seconds shorter than Osborne’s anthem.

Tyson holds his arms outstretched, palms up, not a gladiator now so much as an emperor.

Rooney embraces him.

King rushes in, embracing them both at first, then seizing on Tyson.

Scores of pickpockets, quick and nimble as roaches, descend upon the press and VIP sections.

The ring is like a cattle car now, packed shoulder to shoulder, sway‑ ing dangerously.

“There’s a near riot taking place on the apron in front of us,” says Lampley.

“We just had a body fly over us here,” says “Colonel” Bob Sheridan, calling the international broadcast.

In the midst of the scrum, Tyson finds Spinks, pulls him close, and plants a kiss by his left ear.

Buffer calls for security to clear the ring.

“I can handle chaos,” says Tyson. “I’ve had chaos all my life.” The guy next to Hamill is looking for his wallet.

“Brownsville, all right!” yells the champion, raising a fist. “Brownsville.”

On South Street, in Lower Manhattan, the presses begin to roll with a fresh proclamation, the new emperor’s title, an edition of the New York Post declaring Tyson “the baddest man on the planet.”

Tyson’s at the lectern now. King stands behind him, Robin sits to her husband’s immediate right. As the session began, she clasped his hand in hers and kissed it, as if a maiden whose honor he’d just defended.

“I wasn’t really appreciative of what you guys did to me,” says Tyson. “You tried to embarrass me. You tried to embarrass my family. You tried to disgrace us. As far as I know, this might be my last fight.”

Robin claps.

“Talk, girlfriend!” King bellows.

“He told me that this was going to happen,” says Tyson.

He. D’Amato.

Tyson and Robin duck into the after-party.

“Mike, you motherfucker.”

It’s his sister. She tells him to get her a diet soda.

“Let’s get out of here,” Tyson tells Robin. “Shelly gave me a cheesecake.”

He’s three days shy of his twenty‑second birthday. What can he really see in this moment? His sins? The betrayals that await? The guy who’ll try to shank him in prison? Or the daughter playing tennis?

Nah. None of that.

The future is a religion he cannot believe in.

There is only now: a girl in a red dress, a cheesecake from Junior’s.

And the voice. Devour them both, it commands. And live forever.

From BADDEST MAN: The Making of Mike Tyson, publication date June 3, 2025 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2025 by Mark Kriegel.

Mark Kriegel is a boxing analyst and essayist for ESPN and author of the new book, BADDEST MAN: The Making of Mike Tyson.

esquire