A Crushing Wave of Snow

By the time I caught up with my teammates at an elevation of seventeen thousand feet, the call had already been made to stop and set up camp. That decision saved my life. We’d spent most of the day inching our way up the slopes of Lenin Peak, a 23,406-foot mountain in what was then the Soviet Union, and were still a few hundred yards short of Camp 2, our intended destination. Progress from Camp 1, around three thousand feet below, had been slow in part because we were struggling to breathe in the thin mountain air, but also because it had been snowing for several days, and making headway in the soft snow was hard work.

It was late in the afternoon, and we’d reached a spot where the steep terrain we were climbing gave way to a gently sloping plateau. Camp 2 had just come into view. It looked crowded, dotted with about twenty tents. A few climbers could be seen milling about. Given our slow pace, the traverse there would have likely taken more than the typical half hour that it would under better conditions. So Mark Miller, a renowned English climber and the leader of our six-person expedition, decided to stop for the day. With our shovels, we cut three flat platforms—each large enough for one of our two-person Gore-Tex tents—and set up our own camp, away from the relative bustle of Camp 2.

We spent the next day resting and acclimatizing. Our bodies needed time to get used to the altitude so that we could make a push to Camp 3 and, eventually, the summit. That meant lying on our sleeping bags, melting snow to stay hydrated, and nibbling at bits of food that the general malaise we felt from the altitude made unpalatable.

The monotony was broken by groups of climbers—from Czechoslovakia, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and various parts of the Soviet Union—passing our camp on their way to Camp 2. The Soviets, most of them Russian, were members of the Leningrad Mountaineering Club, the group that was officially hosting us. One of them noted casually that the spot we had chosen for our camp might not be safe from avalanches. Mark paid him no mind. Four climbers from Czechoslovakia chose to camp next to us.

In the afternoon, Mark and our expedition doctor, Mike Cross, headed to Camp 2, to kill time and to take a closer look at the route up to Camp 3. They chatted with climbers of various nationalities and stopped to have tea with four young Israelis we’d befriended over the past few days as we made our way together from Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, to Base Camp and beyond. We’d expected to keep running into them as our two teams worked our way up the mountain. It was the last time any of us saw them alive.

Nowhere to HideWe bolted out of our sleeping bags as soon as we heard it. Mark and Mike had returned a couple hours earlier, and the mountain had been still and quiet. But now what began as a faint rumble quickly grew in intensity. In no time, it had morphed into a terrifying roar that kept growing louder and louder. It reverberated in our stomachs and rattled our bones as we fumbled to open the tent zippers so we could poke our heads out and see what was happening. It was evening but light enough to get a clear look at the slopes above us. Mercifully, there were no signs of immediate danger. But our sense of relief didn’t last.

As we turned our eyes toward Camp 2, we caught sight of the impending disaster. Several hundred feet above the camp, a giant avalanche was gathering mass, strength, and speed. Nearly the entire slope, extending down from the ridge around three thousand feet above, had let loose. In the distance, it looked like a billowing, puffy cloud that was rolling downhill in slow motion. But there was nothing slow about the monstrous onslaught.

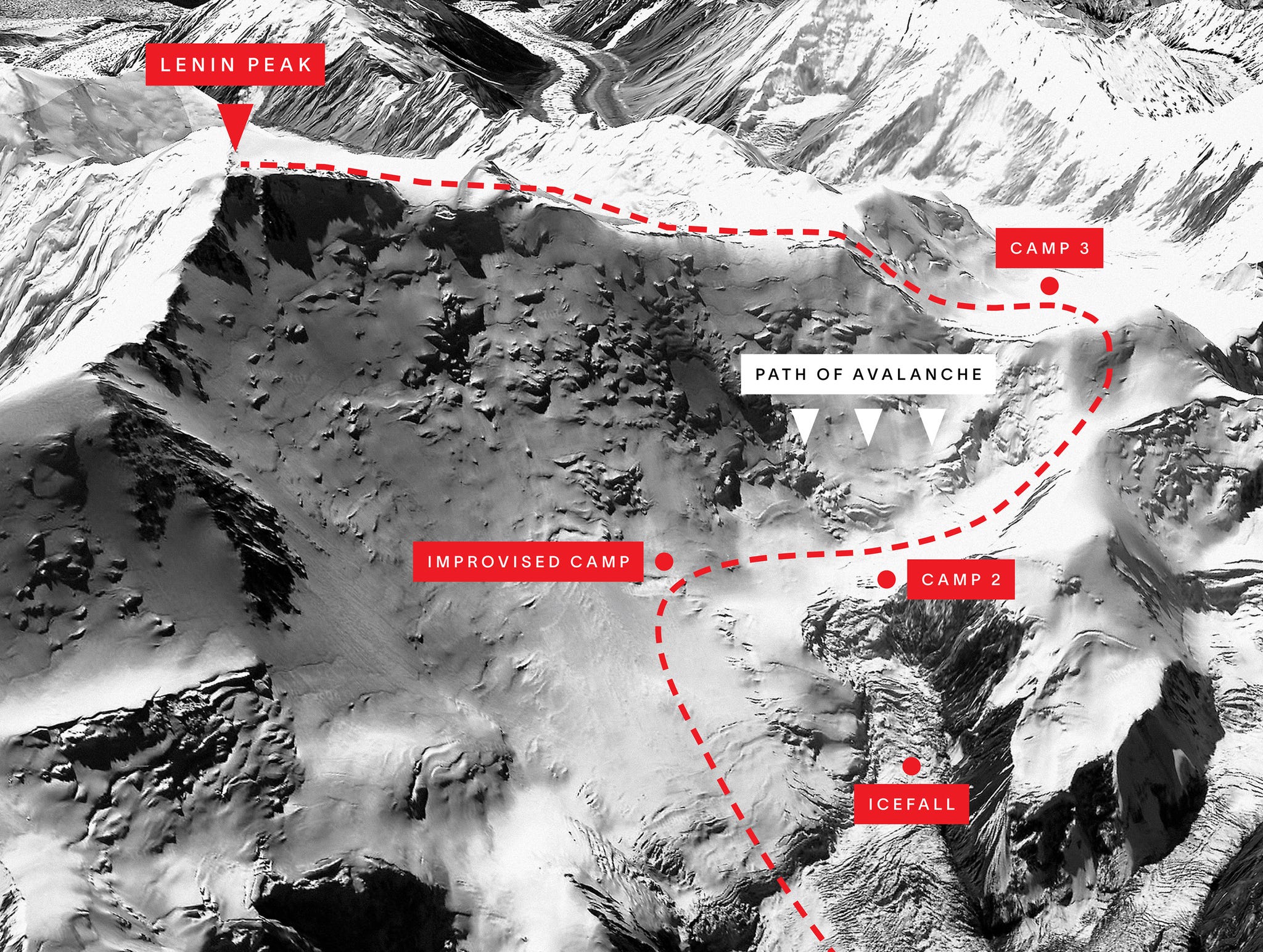

A GIANT PEAK IN CENTRAL ASIA

Rising more than 23,400 feet above sea level, Lenin Peak sits on the border between two former Soviet republics.

At Camp 2, panic had set in. We could see climbers running in all directions in a desperate effort to escape. It was clear they didn’t stand a chance. The avalanche was so wide—we later learned it was nearly one thousand feet across and about a mile in length—that they had nowhere to hide from it and no way to outrun it. There was no safety to be found.

Within seconds, the avalanche seemed to swallow the camp whole, like a giant white wave crashing down. Moments later, the snow settled, and it was over. There was no trace of camp. The climbers had disappeared. Their gear was gone. Their tents were gone. The climber’s trail through the camp was gone. Camp 2 had been completely erased.

We didn’t know it then, but we had just witnessed what is widely believed to be the deadliest accident in the history of mountaineering. On that July evening in 1990—grimly, on a Friday the Thirteenth—forty-three of the forty-five climbers who were at camp were killed by the avalanche. They included twenty-six from the Soviet Union, six from Czechoslovakia, four from Israel, three from Germany, two from Switzerland, and one each from Spain and Italy. To put the scale of the accident in perspective, consider that the deadliest disaster on Everest, the world’s tallest mountain, occurred in April 2015, when a series of avalanches triggered by an earthquake in Nepal killed twenty-two climbers.

At the time of the Lenin Peak avalanche, I was a twenty-seven-year-old seeking adventure. I’d grown up in Argentina, come to the U.S. for college, and gotten bored with a tech job in Silicon Valley. So I’d embarked on a gap year of sorts to backpack around Asia while I considered a potential career shift into the outdoor-travel industry. I’d trekked in India and Pakistan and climbed mountains in Nepal. But Lenin Peak was to be my biggest summit yet.

Narrowly surviving the avalanche didn’t stop me from climbing mountains. Indeed, I spent the next five years helping to guide expeditions all over the world before switching careers again, into journalism. Although the memories never left me, the recurring nightmares eventually stopped. But that tragic day—the luckiest of my life—was vividly etched into my psyche.

It always bugged me that the Lenin Peak tragedy remained virtually unknown in the United States. News stories published at the time of the accident mentioned the terrible death toll. And brief accounts appeared in mountaineering journals. But that was it. The fact that the accident happened on a mountain in a part of the world unfamiliar to most people, and that many of the victims were from the Soviet Union in a largely pre-Web world, meant that it failed to capture the attention of the Western press.

With the thirty-fifth anniversary of the avalanche approaching this summer, I decided the time had finally come to write about it myself. In the process, I revisited searing memories, combed through old journals and foreign press clippings, and talked to former climbing partners, as well as friends and relatives of some of the victims. I also tracked down the two survivors from Camp 2—Alexei Koren, of Russia, and Miroslav “Miro” Brozman, of Slovakia—who agreed to detailed interviews over phone and email that allowed me to piece together the harrowing story of their ordeal.

Delving back into these events caused me to reflect on how we bargain with ourselves to balance risk with adventure. But mostly it transported me back to how terrifying the experience itself really was. Forty-three of my fellow climbers lost their lives in a matter of seconds from a freak occurrence. We’ll never truly know the fear or suffering they experienced in those final moments. But the full story of what happened on the mountain that night deserves to be told.

Crowded on the MountainLenin Peak, named for the Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, is a massive mountain that rises more than four miles from the steppes of Central Asia. It’s part of the Pamir range, the world’s third highest after the Himalaya and the Karakoram. Today, Lenin Peak straddles the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. (In 2006, the latter renamed the mountain after the famous Muslim philosopher Ibn Sina.) When we were there, both countries were still Soviet republics.

The writer’s climbing group set up an improvised campsite just short of Camp 2 on their ascent. That decision saved their lives.

Climbing Lenin Peak on its most common route is not technically difficult. There are no steep sections of rock or ice, and climbers need to rope up only in a few short sections. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. It typically takes a couple weeks to go from Base Camp at Achik Tash, at about 11,800 feet, to the summit, at nearly twice that elevation. To acclimatize, most climbers go up the mountain gradually, in something of a two-steps-forward-one-step-back routine between camps. For example, they might ascend from Camp 1 to Camp 2 bringing food and equipment, descend back to Camp 1 to rest and sleep, and return to sleep at Camp 2 a day or two later. They might follow a similar routine to get to Camp 3. From there, it’s a long climbing day to the summit and back.

Most of the climbing is on snowy or glaciated slopes of various degrees of steepness that require the use of crampons—spiked metal plates that attach to your boots for added traction—and ice axes for safety. High winds, arctic temperatures, and, of course, the challenges of breathing and exercising at altitude add to the difficulty. Yet because of the lack of technical climbing involved, Lenin Peak attracts those who want to test themselves at high altitude or simply want to bag a high peak. For Soviet and Soviet-bloc climbers, it often served as a proving ground before bigger climbs in the Himalaya or Karakoram.

Two other forces made Lenin Peak particularly popular that year. The first was perestroika, the political reform under Mikhail Gorbachev that cracked open the doors of the Soviet Union to more Western climbers. The Israelis we met, for example, were only the second expedition from that country allowed to climb in the Soviet Union. The other force was the rise in guided or commercial expeditions to the world’s highest peaks, including Mount Everest, which began in the late 1980s. Ours was a guided expedition led by Mark Miller and Andy Broom, the cofounders of a new adventure-travel company called Out There Trekking.

I’d met Mark and Andy the previous fall in Nepal, when I climbed a couple of twenty-thousand- and twenty-one-thousand-foot peaks with a British outfitter where they worked as guides. After I spent the following six months backpacking across South Asia, I returned to Nepal and ran into them in a Kathmandu café. They told me they had started Out There Trekking and that their first expedition would be to Lenin Peak in a couple months. When they invited me to join them, I jumped at the opportunity.

Climbing to Camp 2Looking back, the journey to Lenin Peak and Camp 2 was a wonderful window into a specific moment in time. I’d met Mark and Andy in Hoek van Holland, a coastal town in the Netherlands with a train connection to the UK. I joined them in a train compartment whose every spare inch was packed with camping and climbing gear and food. The train ride to Moscow took us through Berlin, where we could see remains of the recently demolished wall, through Warsaw, and across Belarus.

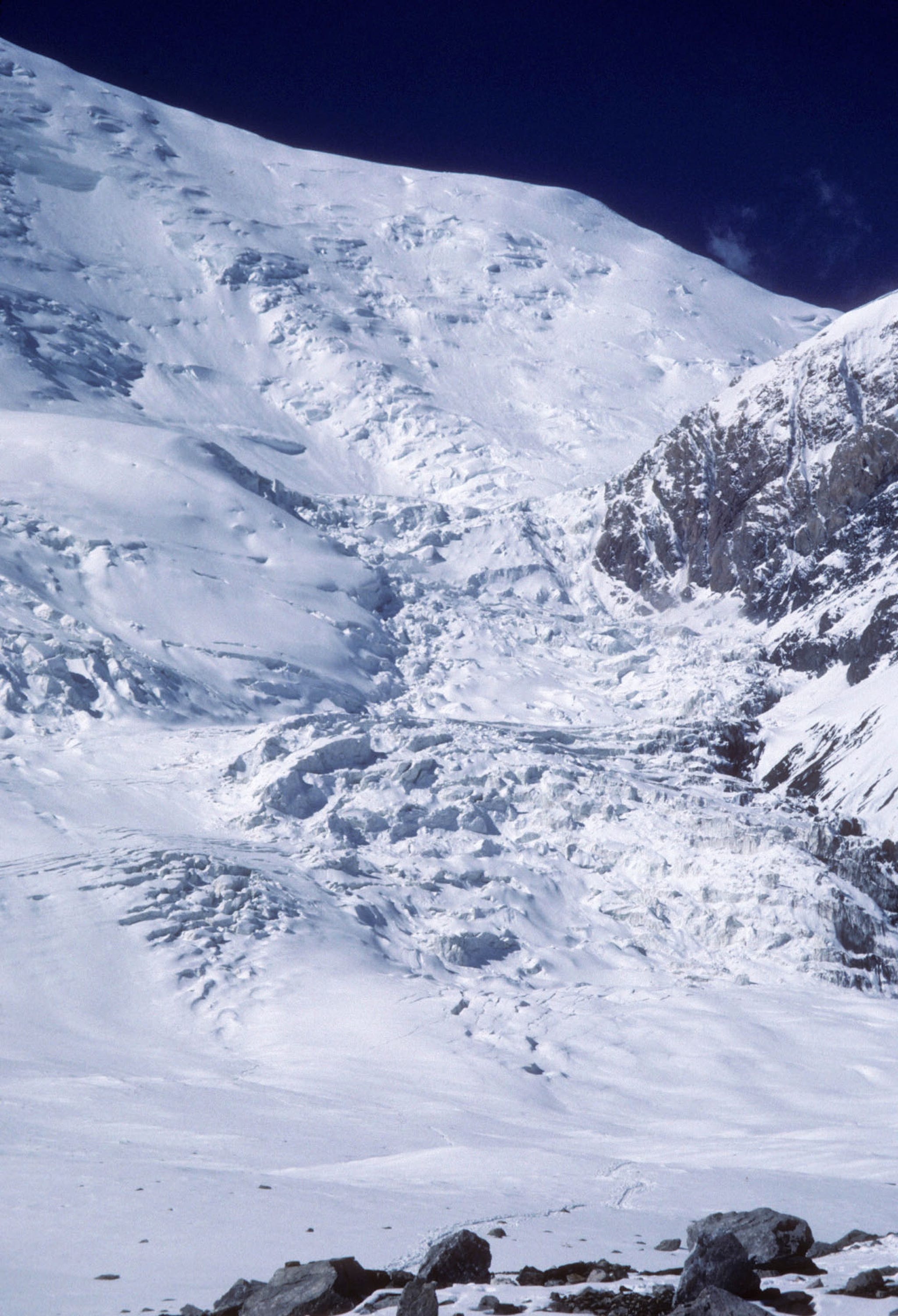

Looking up at Camp 2, known as the “frying pan,” from the writer’s campsite before the avalanche.

Once in Moscow, we met our hosts, Vladimir and Dimitri, from the Leningrad Mountaineering Club. They put us up in an enormous Soviet-style hotel that had been built for the 1980 Olympics and seemed to be all but empty. Our first night there, they insisted on going to one of the hottest restaurants in town—the Soviet Union’s first McDonald’s, on Pushkin Square, which had opened recently. It was one of the most tangible symbols of perestroika and a source of pride for Muscovites. There was a line around the block. We begged them to take us somewhere—anywhere—else, and they obliged.

After a couple days in Moscow, we flew to Dushanbe. At our hotel, we met other climbers, including the team from Israel. A day later, all of us packed into a turbo-prop plane that took us to Djirgital, a small town at the foot of the Pamir. With dusty, unpaved streets featuring a mix of Soviet-era cars and horse-drawn carts and pedestrians in traditional clothing, it had a distinctly Central Asian feel. We camped next to the airport, amid rows of poplar trees. The next morning, we loaded all our gear, and that of other climbers, into an Aeroflot military helicopter that would take us to Base Camp at Achik Tash. About a dozen of us piled onto benches on either side of the chopper. Instead of a closed gate, the rear of the helicopter was protected only by a net made of coarse rope. Our nerves were quickly calmed by the stunning vistas of the mountains that came into view as we gained altitude.

Base Camp was a lush green meadow, dotted with tents. The massive white bulk of Lenin Peak towered above. The next morning, we woke up to a foot of snow on the ground. What we hoped would be a relatively easy hike along the edge of a glacier to Camp 1, where the proper climbing would begin, turned into a slow grind. Laden with fifty-five-pound packs, we did not manage to make it all the way and camped some distance short of it. The next morning, we finished the trek and set up our tents near the Israelis. It was two days later that we would ascend toward Camp 2 only to set up camp before reaching it.

The writer on the mountain before the avalanche.

Camp 2 sits in a spot known as the “frying pan” because of its location at the bottom of a slope that partly encircles it, like a bowl that’s been cut in half. When the sun shines, its glare reflects on the camp from all directions. Just below camp, the smooth slopes that tower above it turn into a steep icefall—a section of a glacier composed of a jumble of ice chunks, known as seracs, separated by gaping chasms. When the untold tons of snow came thundering down, Camp 2 turned into a killing ground in seconds.

After the AvalancheAs the avalanche settled, it completely reshaped the topography of the frying pan. The bowl was replaced by a sloping pile of debris. But we had no time to contemplate the change, let alone to dwell on our shock and confusion. If there was any chance of rescuing anyone, we’d have to act fast. People buried by avalanches rarely survive more than ten to fifteen minutes. So Mark assembled a team of four, including Mike—our doctor—and two Czechoslovaks, and rushed toward Camp 2 to look for survivors. The rest of us packed up our camp and, led by Andy, began to descend as quickly as possible to alert people at Camp 1 and Base Camp. We knew many of the climbers below had teammates at Camp 2.

I was in the group that descended. Within an hour or so, we were overtaken by darkness. After a quick discussion, Andy decided it wasn’t safe to keep going, as not everyone had headlamps. So we set up an improvised camp. Once the tents were up, I walked a few feet away, knelt on the snow, and retched. At dawn the next day, we finished our descent to Camp 1 and started waking up climbers in tent after tent to share the devastating news.

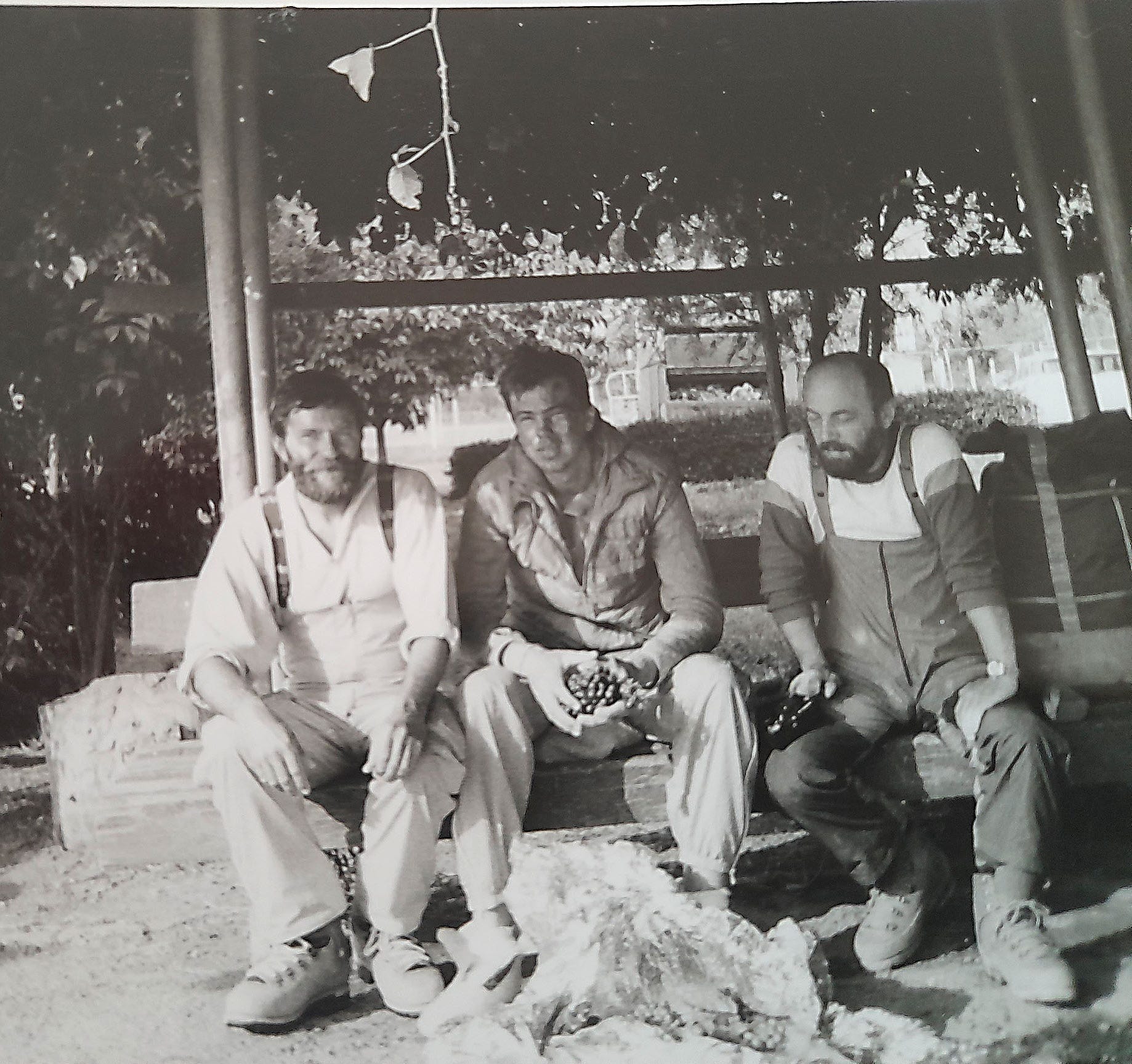

Miro Brozman (center) with two other climbers before ascending Lenin Peak.

Meanwhile, Mark’s team of four had made a quick dash toward the avalanche site. “Time was ticking,” Mike told me in a recent interview. “The first thing we noticed was that everything was rock-solid.” Although avalanches look like fluffy clouds while in motion, their debris hardens almost instantly, making rescues of anyone buried extremely challenging. “It was pretty dark by then,” Mike says. “It was impossible to recognize where anything had been.”

At one point, the rescuers thought they heard faint echoes of voices that seemed to be coming not from anywhere in the frying pan but from the icefall. As they strained to listen, everything quieted down. They decided to head back to camp and return in the morning. “There was nothing for us to do,” Mike says. The morning was no different—not a trace of humans or of their presence there just twelve hours earlier. The team packed up and began their descent, convinced there were no survivors. As it turned out, they were wrong.

Tumbling in the DarkThe avalanche hit Miro with the force of a hurricane. It lifted him off his feet and blasted him in the air. “I could feel the force twisting and flipping me in the air, literally grinding me,” Miro recently wrote in a detailed account of his memories that he shared with me. “Then I lost consciousness.”

Minutes earlier, Miro, a twenty-two-year-old from what was then Czechoslovakia, had been comfortably inside his tent with two of his best friends from childhood, Vlad and Brano. The three had grown up in Slovenská Ľupča, a small town in central Slovakia, about ninety minutes from the Tatra mountains. They met in school and bonded through winter sports, including cross-country skiing, ski jumping, and, eventually, climbing and ski mountaineering in the High Tatras. In the spring of 1990, they ventured farther away, climbing their first peaks in the Austrian Alps.

When they returned home, the local mountaineering club surprised them with an unexpected offer: They’d been selected to join a medical-mountaineering expedition to Lenin Peak. It would include experienced climbers, as well as doctors—fifteen people in all—who would bring equipment to study how low levels of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream affected the onset of altitude sickness.

Like many other groups, they made their way to Dushanbe, then to Base Camp and Camp 1, before descending back to Base Camp. On the morning of the tragic day, Miro and his two friends, along with some other members of the expedition, began climbing back up. They reached Camp 1 and, after a short rest, continued to Camp 2. Along the way, they passed our group. Further up, they came to the aid of a climber from Spain who was struggling with fatigue or altitude and helped him make the last push to the frying pan.

Alexei Koren on Lenin Peak in 2022 holding his old crampon, which he found buried in the snow after thirty-two years.

None of them had been at such a high elevation before, and they were proud of their achievement. “On that day, we climbed about fifteen hundred meters [forty-nine hundred feet] in elevation. We were satisfied and pleasantly tired. It was already evening, but the white snow seemed to illuminate everything,” Miro says. “The three of us fit into our tent, which we had slept in many times before. We made tea, pudding, then tea again. We ate some biscuits.” The three put on almost all the layers of clothing they had. “Tucked in our sleeping bags, we played card games and just lay there talking about the ascent route to the very top.”

When a faint rumble pierced the calm evening, Vlad stuck his head out of the tent. Unable to see anything, he crawled back in. But as the rumble grew to a roar, Brano jumped out and stood in front of the tent. “ ‘It’s coming to us,’ ” Miro remembers him yelling. “I climbed out of my sleeping bag like a rocket and ran in front of the tent to meet Brano. I looked up at the mountain and saw a monstrous white mass of snow coming toward us. I don’t know exactly, but it could have lasted a few seconds. I realized it was over. Important memories from my life flashed through my head.” Then he was hit and thrust into the air. And he blacked out.

Alexei, a thirty-five-year-old Russian climber who was camped nearby, had no warning. One second, he was snoozing; the next, his tent was ripped to shreds, he was ejected from his sleeping bag, and a tremendous force on his back lifted him up and began dragging him down the hill.

In the excruciating seconds that followed, Alexei remembers little other than his intense physical struggle for survival. “I was very strong at the time,” Alexei told me in a recent interview. He also had extensive training, having reached the title of “Master of Sport” for climbing, a Soviet-era classification for athletes that equated to someone being a national champion. Thanks to his strength and experience, he managed to curl into a ball. Caught in a vortex of snow that pummeled him from all directions, he covered his mouth with his bare hands, creating an air pocket that would keep him from suffocating. And he began counting the rolls. One. Two. Three. “I rolled seven times,” he says.

Tents at the writer’s improvised campsite near Camp 2.

Alexei isn’t sure how long or how far he was carried. He says without much conviction that the ordeal lasted perhaps twenty seconds and dropped him a few hundred yards. After the last of the seven rolls, he tumbled from a serac onto soft snow. All of a sudden everything was quiet, and miraculously, the avalanche had not buried him.

Alexei had arrived at Camp 2 that afternoon. It was his second time to reach it on this expedition. A few days earlier he and his expedition mates had come up to bring tents and food and gone back down. Alexei was a veteran of Lenin Peak, having been a fixture of its international climber’s camp. On this trip, he was part of a group of nineteen Soviet climbers from the Leningrad Mountaineering Club who were on Lenin Peak merely as a way to train for a far more ambitious climb: Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth-highest mountain, which straddles the border of Nepal and Tibet.

As it turns out, it was Alexei who had warned our group to reconsider where we had camped. “I told the English guys that it was a very dangerous place,” Alexei says. The spot we had chosen had seen avalanches with some regularity, he told me. Not big ones, like the one that would take out Camp 2, but big enough to bury you, he says.

Just Two SurvivorsAfter regaining consciousness, it took Miro a few seconds to get oriented and realize what had happened. He was lying on his back, with his head pointing downhill and his legs buried in hard snow. Moving was difficult, and he couldn’t see out of his right eye. All he had on were long johns. His torso was bare. “My first sight was of a sky full of stars,” he told me. “After a while, I saw a guy sitting in the snow, holding his head in his hands, a few meters away from me. I started shouting at him, Help me, help me, then in Russian, Pomoshch’, pomoshch’.”

It was Alexei, who after the last tumble off the serac had begun assessing his situation. He was badly battered and very sore but had no broken bones. He was wearing thermal underwear, socks, and a fleece jacket. Detritus from the camp—shredded bits of tents, scattered gear and clothing—were strewn all around.

Alexei rushed over to Miro and, using his bare hands, dug at the snow that had trapped Miro’s legs until he was able to free him. Miro was in much worse shape than Alexei. He couldn’t move his right leg. His pelvis and right shoulder hurt terribly. There was blood under his nose and near his ears. “I just felt like a steamroller had run over me,” he says.

The icefall area below Camp 2 before the avalanche.

Moving quickly, Alexei rummaged through the debris looking for anything that could help them survive. In the process, he came upon a ghastly sight: a pair of lifeless legs sticking out of the snow. The rest of the body was buried in snow that had hardened around it like cement.

After more searching, Alexei found some essentials: a fleece jacket for Miro, a foam sleeping pad, and, amazingly, a lightweight emergency blanket, made out of heat-reflective material. They wrapped it around themselves, and Alexei began yelling for help, following a Russian protocol. “You must call out six times a minute,” he says now. “It’s like a signal that you need help.” There was no answer. After about twenty minutes, he gave up, and the two climbers huddled for the night.

Miro had learned some Russian in grade school, so the two were able to communicate. “We talked a little bit,” Alexei says. “Sometimes we slept a little bit, then we would wake up. Then we’d sleep.” His mind kept circling back to the same questions. “What happened? Was all the camp smashed by the avalanche? Or only half? There was no answer to these questions in my head,” he says.

“Fortunately, the night was not so cold,” Miro told me. Not so cold, at that elevation, meant the night was survivable but far from comfortable. It was below freezing, and the two lacked proper winter gear or clothing. “We were facing each other and warming each other’s legs and arms. My teeth were chattering so much from the cold that it was quite audible.” His thoughts turned to his childhood friends and the likelihood that they had not survived. “I came here with my best friends,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine returning home without them. Tears welled up in my eyes. It was the longest night in my life.”

An Agonizing DescentFor his part, Alexei was thinking about how they would make their way down. There was no prospect of descending in the night. The terrain they were on was far too dangerous. The snow was knee-deep in places and probably hid gaping crevasses that could swallow them whole. There were huge seracs that could topple and crush them, and any descent involved navigating steep, slippery slopes in their socks.

At first light, temperatures began rising and their predicament became clearer. “Alexei started looking for a way in the impassable icefall,” Miro says. “He would find his way between some cracks, and I would try to follow him.” Miro’s progress was especially slow, because, unable to walk, he was limited to crawling through the snow. “It didn’t work very well,” he says. A few times, Alexei would descend a short distance, then climb back up to where Miro was and drag him down on top of a sleeping pad. At times, the fog was so thick that he couldn’t see if the terrain in front of him inched up or down, so he would throw a snowball and listen for its impact.

Rescuers and doctors on Lenin Peak after the disaster.

“I have no idea how far we ‘walked,’ ” Miro says. “We just walked, resting here and there. We were thirsty. Sometimes we felt desperate. But I wanted to live, so I always found strength in myself. I didn’t even understand where that energy was coming from.”

Even so, that strength and that energy were not limitless. At some point in the afternoon—Alexei believes it was around 5:00 p.m.—they reached a level spot and Miro said he couldn’t go on. “He was very tired and had no strength at all. He lay on the mat. I covered him in the blanket and continued descending on my own,” Alexei says.

After another couple hours of slow downhill progress, Alexei turned the corner of a serac and a wave of relief flooded over him. Not far away, a climber was ascending toward him. It was an Estonian mountaineer whom Alexei knew from the international camp. Then another climber appeared, and another, and another. His ordeal, or at least the worst of it, was over.

“It was a big group,” Alexei says of the rescuers. Many were Soviets, but there were also some members from Miro’s medical-mountaineering expedition. He told them Miro was a few hundred yards higher, and several of the rescuers headed that way, following Alexei’s tracks. The others gave Alexei food and warm clothes. One of them, a friend he knew from Krasnoyarsk, a city in Siberia, took apart her mountaineering boots—they are typically made of a hard, plastic outer shell and a soft inner bootee—and gave Alexei the outer shell. Alexei was clipped onto a rope, and the group began descending, his friend in her inner booties and Alexei in the hard shells. They were ill fitting but a huge improvement over his socks. “It was difficult,” Alexei says. “But I wanted to go down. I knew there was lemonade at camp, and that’s what I was dreaming of.” It was around 1:00 a.m. when they arrived. Amazingly, Alexei had no frostbite, no broken bones, and no visible signs of the ordeal other than a massive and very painful bruise on his back.

Meanwhile, Miro had been bracing himself for another night on the mountain, this time alone, unsure whether he would survive. As if by miracle, the rescue team appeared just as it was getting dark. It included at least one doctor from his expedition. “They dragged me to a plateau on the glacier, where they pitched tents,” he says. Descending in the dark would have been too dangerous. “I received medical treatment, blood-circulation medications, analgesics,” he says. “I was glad to be among my own.” The rescuers gave him dry clothes and something to drink. And they assessed his condition, which included frostbite on his toes, various bruises, and possibly a broken spine but without a spinal-cord injury. They also looked for other survivors but didn’t find any. Early the next morning, the rescuers loaded Miro onto a metal sled and descended to Camp 1, where he was reunited with Alexei. A helicopter took them to Base Camp and on to a hospital in Osh, the second-largest city in Kyrgyzstan.

As he reflects on his ordeal, Miro knows how much he owes Alexei. “If it wasn’t for Alexei, I definitely wouldn’t have dug myself out of the snow,” he says. “He basically saved my life.”

The AftermathThere are no reliable, comprehensive records of all the mountaineering accidents in the world. But the avalanche on Lenin Peak is widely believed to be the deadliest accident in the history of the sport. It devastated friends, families, and tight-knit climbing communities from Leningrad—now St. Petersburg—to Tel Aviv, where the victim’s friends and relatives still gather annually to remember them.

In prior years, scores of climbers had stayed at Camp 2 on their way to the summit of Lenin Peak. The frying pan was largely considered safe. Tragically, on that day, it wasn’t. “It’s what we call a low-probability, high-consequence event,” says Christian Santelices, a veteran mountain guide from Jackson, Wyoming, who teaches avalanche-awareness courses for the American Avalanche Institute. “They happen so rarely that they are outside of our historical frame of reference. But when they happen, they can be catastrophic.”

Alexei Koren (in yellow) in 2022 on a recovery expedition searching for remains of fellow climbers to bury.

The trigger that set off this low-probability event is thought to have been an earthquake in northern Afghanistan, some 150 miles to the south. The shaking likely dislodged a serac that fell on a slope loaded with layer upon layer of snow that had accumulated over the years, plus the fresh snowfall, triggering the monstrous avalanche. Like any avalanche this big, it was preceded by a powerful air blast that swept all the climbers and all their equipment off the frying pan and onto the icefall. Then the avalanche buried most of them in a mass grave of quickly hardening snow and ice.

Over the years, that mass grave moved down the mountain at a glacial pace as the icefall—like all glaciers—inched its way downhill. In 2007, seventeen years after the avalanche, grim remains from Camp 2 began appearing amid the melting ice, not far from Camp 1. There were pieces of climbing equipment and clothing, shreds of tent fabric, pots and portable stoves and passports. There were also bones and mangled body parts, some identifiable, others not. Over the next few years, teams from various countries organized recovery expeditions. Alexei felt it was his duty to be part of them and has since gone on five of the expeditions. “You need to do this,” he says. “These are your friends. You don’t know if someone is from Russia or Switzerland, but you must bury them.”

Climbers who go to Lenin Peak these days walk past a memorial plaque with the names of the forty-three victims affixed onto a boulder at Base Camp. The partial remains of an unknown number of climbers have been buried nearby. Those who make it to Camp 2 will find that it has been moved about 300 yards to a spot that’s higher and on the edges of the frying pan. It’s commonly considered to be a safer location. And yet Alexei told me it’s in a spot that was swept in the 1990 slide. “It was very wide,” Alexei says of the avalanche. “Three hundred meters wide.” But he added that he’s not too concerned about the danger. “It was the only avalanche in seventy years. There’s no way it will repeat itself. I don’t think so.”

Everyone I talked to who was on Lenin Peak at the time of the avalanche continued climbing. I joined Andy and Mark at Out There Trekking. For the next four years, I helped to organize, support, and lead mountaineering trips in Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nepal, Pakistan, and Russia. (Tragically, Mark died a couple years later, when an Airbus A300 crashed outside Kathmandu, killing all aboard. The plan was for me to meet him there to lead an expedition to Kangchuntse, or Makalu II, a 25,187-foot peak.)

A memorial plaque at Base Camp with the names of the forty-three avalanche victims sits next to a burial site for their remains.

Miro recovered from his injuries quickly and returned to the mountains. “I never stopped climbing,” he says. He turned to rock climbing and competitive ski mountaineering. He says he became more careful and decided not to return to high-altitude peaks, limiting his adventures mostly to the Tatras. Just months after the avalanche, Alexei went on the Cho Oyu expedition in Nepal, with a much smaller team from Leningrad than originally planned. They were forced to turn back shortly before the summit. When I asked him whether he thought of quitting after the avalanche, he replied almost before I was able to finish the question. “No,” he blurted out. “It was not my mistake.”

That’s glib, I thought at first. But as I sat with it, I realized it wasn’t that different from my own rationale. I loved climbing not because of its inherent danger but in spite of it. I climbed conservatively, trying to minimize risks. I often turned back not far from a summit when continuing didn’t feel safe. And deep inside, I had a sense that, if I did all that, I’d be fine. If I exercised the proper caution and didn’t make mistakes, I would be in control.

Perhaps the avalanche should have disabused me of that idea. I’m glad it didn’t, even though years later, when I would tell the story to friends, the typical reaction was “And you decided to become a professional mountain guide after that?” My climbing years were some of the most fulfilling in my life and shaped who I am today. High-altitude expeditions were always hard: ferrying huge loads in extreme conditions; contending with subzero temperatures and gale-force winds; and suffering the chronic malaise, nausea, and headaches of mild altitude sickness. Lying in my tent on a particularly miserable night, I would find myself questioning my choices. But it was always the magical moments that stayed with me: a stunning sunrise above the clouds; inching up an icy slope by moonlight on a clear night; the camaraderie built on teamwork; the indescribable satisfaction of pushing my limits; and, perhaps most of all, the feeling of adventure from going where few had gone before. As soon as an expedition was over, I would start dreaming of the next, hoping to test myself on a harder, higher peak.

One day, that changed. I had been to around twenty-three thousand feet a handful of times and realized suddenly that I’d had my fill. I no longer wanted to climb anything higher. I’d continue adventuring in the wild in many ways but not at high altitude. Looking back, I am immensely grateful that I got to climb in some of the most remote, wild, and beautiful corners of the world. And, of course, I know that I’m alive only because I was unimaginably lucky—on that fateful climb as well as others that went off without incident—while too many others were not.

It’s a feeling I share with Alexei. “I had some bad luck,” he says. “Then I had a lot of good luck.”

esquire