The Britney backlash: Why does the old motto "sex sells" still hold, Sophie Gilbert?

The sexualization of female pop stars is the most reliable way to sell records. The most recent example after Britney and the like: Sabrina Carpenter. What does this do to us women? US cultural critic Sophie Gilbert has the answers.

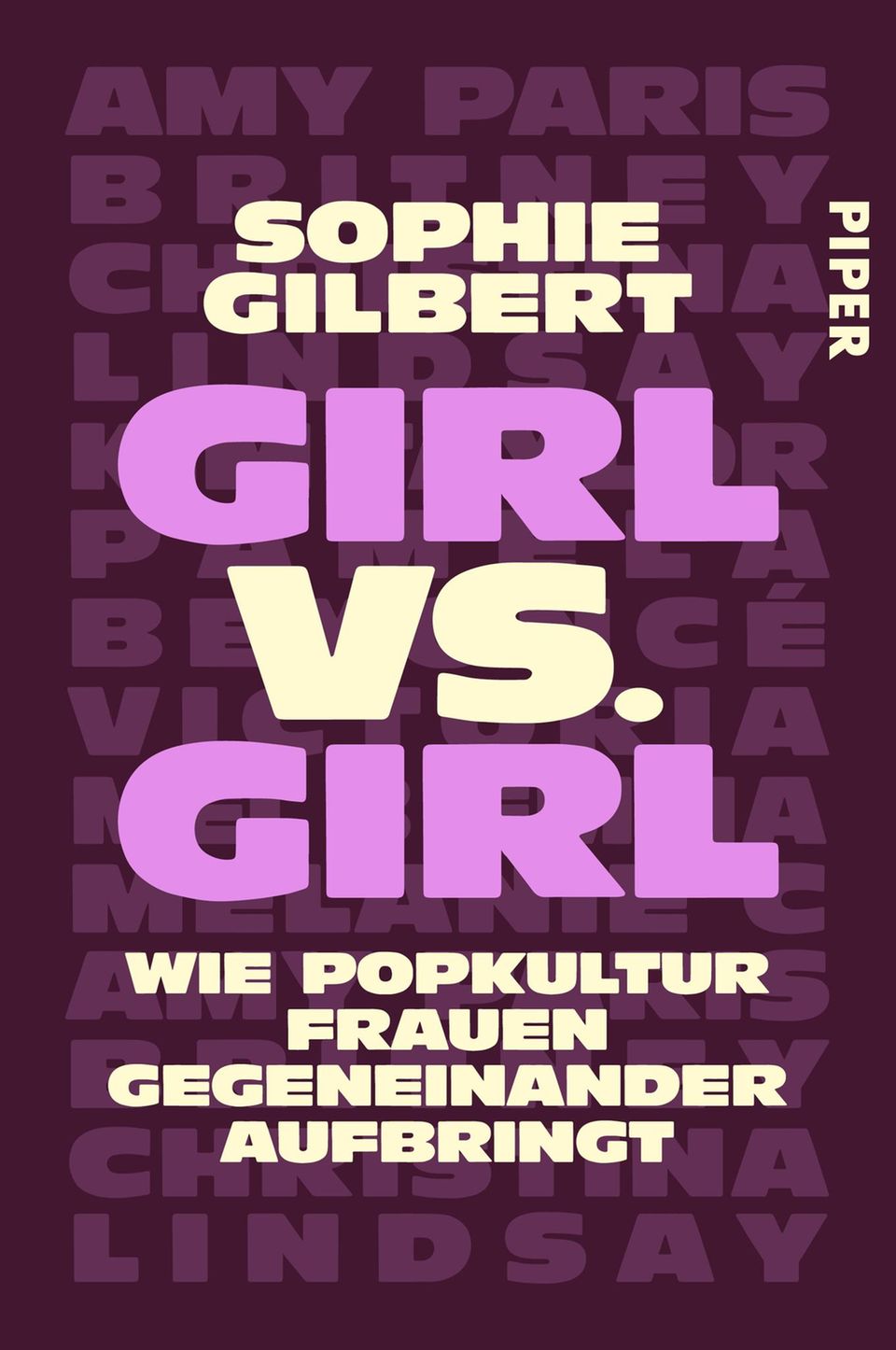

There was much whispering and discussion, and social media comment sections were overflowing when American singer Sabrina Carpenter unveiled her new album cover, presenting herself as a willing sex object. Some saw it as a reenactment of a male fantasy, while others interpreted the photo as empowerment. We asked award-winning US cultural critic Sophie Gilbert, whose social analysis "Girl vs. Girl" has just been published in German. In it, the journalist examines how the objectification of women in the media shapes us—or, more accurately, how it messes us up. And whether we, who grew up with Britney and the like, can't help but find this awful.

BRIGITTE: Ms. Gilbert, can we really call it empowerment when artists like Sabrina Carpenter today commercialize their sexuality, albeit self-determined, but still adapted to the (power) fantasies of the patriarchy?

Sophie Gilbert: What's most exciting about Sabrina Carpenter's current album cover, for me, is the reaction to it. Most critics aren't angry that it's sexualized. They're more bothered by the gender relations in the image—the way Carpenter is kneeling submissively, her hair being pulled, on an album cover titled "Man's Best Friend." What Carpenter is trying to say with it—that's hard to know without asking her directly—and how subversive or ironic she means it.

True.

Many see the image embedded in a media context that represents a step backward for women, in a culture where misogyny is flaring up again. So, the fact that an artist would deliberately provoke with such an image is nothing new. But the measured, considered backlash online is progress for women as a whole. We are no longer afraid to clearly express our opinions or to object.

How do today's artists like Carpenter differ from the highly sexualized teen stars of the early 2000s like Britney Spears or Christina Aguilera, with whom our generation grew up?

For me, the sexualized side of Carpenter's public persona has always been an exaggeration, a bit absurd, and fun. The new cover feels different—she comes across less as a powerful subject and more as a traditionally passive object—like Britney once did.

That's how I feel, too. And this "object" also completely conforms to traditional beauty ideals. Super-thin, super-blonde, super-sexy.

The renewed fixation on very slim, thin bodies also surprised me. We've made progress in body positivity, or at least body neutrality—viewing one's own body with gratitude or acceptance instead of despising it. At the same time, I see parallels to the sexist comedies of the 2000s in some male-dominated online communities, where men fight for recognition and see women as sex objects at best, and enemies at worst.

The "weight loss injection" has brought us dangerously close to the fat-shaming culture of the 2000s. Will this decades-long ritual of self-loathing ever end?

I sincerely hope so, but a lot of it feels familiar. The language on SkinnyTok, the intentionally shaming tone of influencers, the fetishization of eating disorders – just like in the 2000s. For women, this could also be an attempt to maintain control in an increasingly fragmented, chaotic culture. My book was meant to illuminate past patterns, warn, and show: As long as we don't completely reject them, they will always return.

What might a truly emancipated approach to female sexuality in pop culture look like – beyond the superficial "sexy sells" narrative?

This would have to be a genuine exploration of desire and experimentation for women. In the 2000s, sex was everywhere, but mostly as a performance for male gratification, which alienated many women from their actual desire. Female desire is a far too underexplored and misunderstood topic. I wish there were more artists like Chappell Roan, who constantly address sex but don't care what men think.

You write that it comforts you that many young women today view trends like the "tradwife" movement or 12-year-old skincare influencers with skepticism and critically question them. What could tempt women to slip into old gender roles?

There have always been women who prefer to accept the patriarchal status quo rather than constantly fight against it. I can even understand that. Feminism means having the freedom to choose for ourselves. But those of us who want this freedom are stuck in an online world that rewards provocation and conflict. We shouldn't forget: Most "tradwives" are performers and represent only a small fraction of women, despite their great influence.

After reading your book, I was disturbed by how often I had submitted to the (sexual) desires of the patriarchy. Apparently, I unconsciously imitated what pop culture presented to me as "normal" in my youth – with films like "American Pie" or "Clueless." It was all about money, beauty, and performance in bed. What does it do to us to grow up with such images? Do we still carry the misogyny of that time within us, and does that make it harder for us to critically evaluate women like Sabrina Carpenter today?

We learned that women are sex objects. Sex—as men want it—became our primary currency for gaining power in a patriarchal world. We also learned that we must compete with other women for that power. They were, at worst, our enemies, never our allies.

More and more feminists today are saying they're tired of being "sexy"—to reject this system. I felt the same way after reading your book.

I can relate to that. I'm in my early 40s and have young children—and most days I don't have time to worry about that. And that can be very liberating. For me, self-presentation is less about appearing sexy or powerful and more about feeling good about myself. It's about finding joy and freedom, expressing myself as I am and what I want—not who I want to impress. It's creativity, experimentation, and self-expression.

Do you agree that refusal can be the most radical form of female empowerment? Absolutely. Refusal is the be-all and end-all. It is everything. The rejection of the flawed conditions of womanhood is the history of feminism.

"White Lotus" star Sydney Sweeney recently started selling soap made from her bathwater and is making a lot of money. She talks about how exhausting it is to be constantly sexualized for her blonde hair and large breasts – yet she still profits from it. Doesn't this create a vicious cycle? Female stars have the platform and freedom to do what they want with their fame. We, the audience, have the freedom to be critical and speak our minds. Lately, I've seen so many women do this in very satisfying and new ways. Like you did with Sabrina Carpenter.

Brigitte

brigitte

%2520Hotels%2520Griechenland.jpg&w=3840&q=100)